In This Issue:

- SCOTUS Hears Oral Argument in Challenge to Constitutionality of CFPB’s Funding

- Court Rules in Favor of HUD in Disparate Impact Rule Case

- Alan Kaplinsky Authors American Banker Article on CFPB v. CFSA

- Respondents File Brief Urging SCOTUS Not to Overrule Chevron

- CFPB Revisits Adverse Action Notice Requirements When Using Artificial Intelligence or Complex Credit Models

- This Week’s Podcast Episode: Federal Court Rules CFPB Cannot Use UDAAP Authority to Regulate Discrimination: A Close Look At the Decision and Its Implications

- FinCEN Issues Small Entity Compliance Guide for Corporate Transparency Act

- CTA Round-Up: FinCEN Proposes Extended CTA Filing Deadline, Revised Reporting Form, and Privacy Act Exemption; Expands CTA FAQs; and Requests Comments on FinCEN Identifier

- CFPB Launches FCRA Rulemaking to Eliminate Creditor Use of Medical Debt

- CFPB Releases Updated 1071 Small Business Lending FAQs

- CFPB Releases 2022 Mortgage Market Activity and Trends Report

- Connecticut Issues Guidance Clarifying the Applicability of its Small Loan Act to “True Lenders” and Earned Wage Access Providers

- Did You Know?

SCOTUS Hears Oral Argument in Challenge to Constitutionality of CFPB’s Funding

On the morning of Oct. 3, the U.S. Supreme Court held oral argument in Community Financial Services Association of America Ltd. v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a case we have been following closely on Consumer Finance Monitor because of its profound potential implications for the future of the CFPB. In the case, the Court will rule on whether the CFPB’s funding mechanism violates the U.S. Constitution’s Appropriations Clause and, if so, what the appropriate remedy should be. Elizabeth Prelogar, the Solicitor General, argued for the CFPB, and Noel Francisco, a former Solicitor General, argued for the CFSA.

In the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress provided that the CFPB would receive annual funding from the combined earnings of the Federal Reserve System. Each year, the Federal Reserve Board is directed to transfer to the CFPB an amount determined by the CFPB Director to be reasonably necessary to carry out the CFPB’s authorities, with that amount not to exceed 12% of the Federal Reserve’s total operating expenses as reported in 2009 (approximately $600 million) as adjusted for inflation.

The essence of the CFSA’s position is that the CFPB’s funding violates the Appropriations Clause because it allows the CFPB, in perpetuity, to self-determine how much funding it needs each year subject only to an illusory cap set so high that the CFPB has never come close to hitting it, a unification of “sword and purse” contrary to the intent of the Framers. CFSA argues that the funding of historical and other modern agencies can be distinguished because those agencies operated or operate on a fee-for-services model, whereas the CFPB’s funding mechanism is unprecedented. According to the CFSA, if the Appropriations Clause is read to allow the CFPB’s funding mechanism, it would leave Congress free to write the President a blank check payable each year forever to set the budget for the entire federal government (except the Army, because of a separate Constitutional Clause limiting appropriations to the Army to terms no longer than two years).

The essence of the CFPB’s position is that the Appropriations Clause’s text does not limit Congress’s authority to determine the specificity, duration, and source of appropriations and that the CFPB’s funding mechanism is consistent with the constitutional text, history, and precedent. According to the CFPB, since the nation’s founding, Congress has made lump-sum appropriations committed to the discretion of the Executive Branch, provided federal agencies with standing appropriations that remain in place unless and until Congress repeals them, and funded agencies through fees, assessments, investments, and other similar sources. Because Dodd-Frank prescribes the amount, duration, source, and purpose of the CFPB’s funding, it satisfies the classic elements of an appropriation and falls easily within Congress’s historical practice.

The focus of many of the conservative Justices’ questions was on what are the limits that the Appropriations Clause places on Congress and the role of appropriations in the separation of powers. The questions asked by Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, and Alito suggested that they were concerned about the implications of a reading of the Appropriations Clause that places as few constraints on Congress as would the CFPB’s reading of the Clause, such as allowing standing or uncapped appropriations.

Chief Justice Roberts indicated that the CFPB had “a very aggressive view of Congress’s authority under the Appropriations Clause” and that he “didn’t see any compelling historical analogues” to the CFPB’s funding mechanism. Similarly, Justice Alito asked the Solicitor General whether the unprecedented nature of the CFPB’s funding (i.e. an agency that draws its money from another agency) was relevant to its constitutionality. Justice Thomas, however, suggested that the novelty of the CFPB’s funding did not raise constitutional problems, stating that that even if Congress has “never gone this far [it] is not a constitutional problem” but “may be a problem with analogues.”

Justice Barrett’s questions suggested some skepticism with the CFSA’s position, such as whether there is textual support for the limits on Congress’s appropriations power asserted by CFSA or whether standing appropriations are constitutionally problematic. Justice Kavanaugh appeared to take issue with the CFSA’s characterization of the CFPB’s funding as “perpetual” stating:

I’m having trouble with [that characterization] because it implies that it’s entrenched and that a future Congress couldn’t change it. But Congress could change it tomorrow and there’s nothing perpetual or permanent or–about this.

Justice Kagan’s, Justice Jackson’s, and Justice Sotomayor’s questions suggested they were comfortable with the CFPB’s funding structure, with Justice Jackson suggesting that it was CFSA’s burden to establish what limits exist on Congress’s appropriations power and that the CFPB’s funding mechanism violated those limits. Justice Jackson also suggested that an absence of historical precedent for the CFPB’s funding mechanism would not be sufficient to establish that Congress did not have the prerogative to structure the CFPB’s funding as it did in Dodd-Frank. Justice Kagan took issue with the CFSA’s characterization of the CFPB’s funding cap as “a number so high it’s almost never relevant.” She called $600 million “a rounding error in the federal budget” and suggested that, as the CFPB’s programs develop over time, its funding needs could reach the cap. In addressing a CFSA argument that the lack of durational limits on the CFPB funding is particularly problematic, Justice Sotomayor stated “I’m sorry. I’m trying to understand your argument, and I’m at a total loss.”

It is noteworthy that despite the potential implications of a ruling by the Supreme Court that the CFPB’s funding is unconstitutional, only Justice Sotomayor asked questions about what the appropriate remedy would be for a constitutional violation. In particular, Justice Sotomayor asked whether the Fifth Circuit’s implicit sweeping remedy of invalidating not only the payday lending rule but all other CFPB actions was appropriate. She also asked about the possibility of using a severability analysis.

We can sometimes predict the outcome of a Supreme Court case based on the oral argument and the tenor of the questions asked by the Justices. However, particularly in light of what seemed to be restrained questioning of the Solicitor General by the conservative Justices, this case does not readily allow us to predict an outcome. All we can say with certainty is that the Court will issue a decision before the end of its term in June 2024.

On October 17, 2023, from 2:00 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. ET, Ballard Spahr will hold a special webinar roundtable, “The U.S. Supreme Court’s Decision in CFSA v. CFPB: Who Will Win and What Does It Mean?” The webinar brings together six attorneys who filed amicus briefs with the Supreme Court. To register, click here.

Richard J. Andreano, Jr., John L. Culhane, Jr., Michael Gordon & Alan S. Kaplinsky

Court Rules in Favor of HUD in Disparate Impact Rule Case

More than 10 years after the filing of the initial complaint challenging the 2013 disparate impact rule (Rule) adopted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) under the Fair Housing Act (Act), the federal district court in Washington, DC granted HUD’s motion for summary judgment. The two plaintiffs that filed the lawsuit are the insurance industry trade associations, the American Insurance Association and the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC), although ultimately the case was pursued only by NAMIC. Members of the plaintiff associations issue homeowners property insurance, which is covered by the prohibitions against discrimination under the Act. The judge in the case is Richard Leon, a Senior District Judge appointed by President George W. Bush.

The Rule sets forth a burden shifting standard for disparate impact claims under the Act:

- The plaintiff in a lawsuit or charging party with an administrative complaint filed with HUD (plaintiff) has the burden of proving that a challenged practice caused or predictably will cause a discriminatory effect.

- If the plaintiff satisfies such burden of proof, the defendant in a lawsuit or responding party with an administrative complaint filed with HUD (defendant) has the burden of proving that the challenged practice is necessary to achieve one or more substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interests of the defendant.

- If the defendant satisfies such burden, the plaintiff may still prevail upon proving that the substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interests supporting the challenged practice could be served by another practice that has a less discriminatory effect.

HUD adopted the Rule at a time when it appeared that the Supreme Court would address for the first time whether disparate impact claims may be brought under the Act. Two cases addressing the issue that the Supreme Court agreed to hear ended up settling before oral arguments were held. A third case, Texas Department of Housing & Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, Inc., ended up being the charm. In a 5-4 decision handed down in 2015, with former Justice Kennedy writing for the majority, the Court ruled that disparate impact claims may be brought under the Act. In so ruling, however, the Court indicated that appropriate safeguards were necessary to protect defendants from inappropriate claims of disparate impact. In this regard, the Court made several points:

- A claim based on statistical disparity fails without a showing of causation. That is, the plaintiff must show a causal link between an act or practice of the defendant and the statistical disparity.

- A robust causality requirement ensures that racial imbalance does not, without more, establish a prima facie case of disparate impact and, thus, protects defendants from being held liable for racial disparities they did not create.

- Governmental or private policies are not contrary to the disparate impact requirement unless they are “artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers.”

- Courts should avoid interpreting disparate impact liability to be so expansive as to inject racial considerations into every housing decision.

- These limitations are also necessary to protect defendants against abusive disparate impact claims.

While the Court acknowledged the existence of the Rule, it did not base its decision on the Rule.

In response to the Inclusive Communities decision, the plaintiffs in the lawsuit challenging the Rule amended their complaint. While the amended complaint acknowledged that disparate impact claims could be brought under the Act, the plaintiffs asserted that the Rule nonetheless was inconsistent with the Act and the Inclusive Communities decision. Oral arguments were scheduled for February 2017, but the case was stayed as the Trump Administration was now in place and new leadership at HUD and the Department of Justice needed to be nominated, confirmed and then brought up to speed on the case. Then the Trump Administration decided to revisit the Rule and issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking in May 2018 requesting comment on whether the Rule was constituent with the Inclusive Communities decision. The case continued to be stayed.

In August 2019, HUD proposed to amend the Rule to provide for a new burden shifting framework and make other changes that HUD asserted would make the Rule consistent with the Inclusive Communities decision. In September 2020, HUD issued a final revised disparate impact rule. That final rule was quickly challenged in court by consumer groups, and in October 2020 a federal district court in Massachusetts stayed the effective date of the revised rule and enjoined the enforcement of the revised rule.

Enter the Biden Administration. In a memorandum issued on January 26, 2021, President Biden ordered HUD to “as soon as practicable, take all steps necessary to examine the effects of” the 2020 rule. That led to HUD proposing to reinstate the Rule, and ultimately doing so through a final rule issued in March 2023. After all of this activity, the lawsuit challenging the Rule, which was now reinstated, moved forward.

The court first addressed certain defenses raised by HUD that were unrelated to the merits of the case, namely whether NAMIC had standing and whether the case was ripe for review, and the court decided in favor of NAMIC. The court then turned to four substantive claims made by NAMIC, with the court rejecting all of the claims.

The first claim was that the Rule is not authorized by the Act to the extent that it imposes a disparate impact requirement on insurers’ underwriting and rating practices. The complaint asserted that the trade association members make race-blind underwriting and rating decisions for property insurance, and that under the Rule, in order to ensure that their policies and practices did not cause or perpetuate a disparate impact, the members would be compelled to collect data on protected characteristics such as race, consider that data, and make classification and rating decisions that take into account membership in protected groups. Addressing this claim, the court stated that it is hard to see how the Rule causes the “pervasive consideration of prohibited characteristics that NAMIC fears is inevitable.” The court added that nowhere does the Rule “require those engaging in housing practices to collect or use data on individual’s protected characteristics. Rather, as HUD points out, the initial burden is on the plaintiff to provide—through data or otherwise—that a housing practice actually or predictably results in a disparate impact.” (Citations omitted.)

The second claim was that the trade association members are heavily regulated under state laws that (1) substantially limit insurers’ discretion to make underwriting and ratemaking decisions, and (2) also dictate what criteria insurers may use to classify risks. As a result, the complaint then asserts that disparate impact claims against insurers based on underwriting and rating decisions cannot lie under the Act. The complaint also points to the federal McCarran-Ferguson Act as supporting this conclusion. The McCarran-Ferguson Act generally reserves the regulation of the insurance business to the states, and provides that a federal law cannot be construed to “invalidate, impair or supersede” state insurance laws unless the federal law involved “specifically relates to the business of insurance.” The complaint notes that the Act does not specifically indicate an intent to override the authority of states to regulate the business of insurance, and that imposing a disparate impact requirement on insurers’ underwriting and ratemaking decisions would in effect invalidate, impair or supersede state insurance laws.

The court acknowledged the existence of the state law restrictions on the underwriting and ratemaking determinations of insurers. However, the court believed that the state law restrictions, together with the robust causality requirement under the Inclusive Communities decision, are actually favorable for NAMIC’s members. The court states that if “an insurer is sued under a disparate-impact theory of liability, it can try to show that a state law prohibits (or requires) certain underwriting or rating decisions in a way that severs the casual connection between the insurer’s practices and the disparate impact. If successful, the insurer should be able to get the case dismissed. But that does not make the . . . Rule unlawful or, somehow, categorically inapplicable to insurers.” (Citations omitted.)

The third claim was that the Rule conflicts with the Act because it allows a claim to be established solely on statistical disparities. As noted above, in the Inclusive Communities decision the Supreme Court made clear that a claim based on statistical disparity fails without a showing of causation. The court responded to this claim in part as follows:

“[C]ontrary to NAMIC’s position, proof of causation is exactly what the . . . Rule requires of plaintiffs at the prima facie stage. To be sure, the Supreme Court specifically called out statistical disparities as being insufficient alone to establish causation at the prima facie stage, and the . . . Rule does not. But the . . . Rule’s legal standard can still be, and is in fact, consistent with Inclusive Communities even if the Rule does not include the same depth of explanation as does the judicial opinion.”

The court concluded that the Rule simply does not allow a prima facie showing with nothing more than evidence of statistical disparities.

This portion of the court’s decision is interesting. The court admits that the Rule does not expressly provide that statistical disparities alone are insufficient to establish causation at the prima facie stage, and that the Rule does not set forth the legal standard of causation at such stage with the same depth of explanation as the decision in Inclusive Communities. It is not hard to see that another court may find those variances to mean that the Rule is in fact inconsistent with the Inclusive Communities decision. When we previously reported on HUD’s reinstatement of the Rule, we noted various ways in which the Rule differed from the Inclusive Communities decision. For example, in the Inclusive Communities decision the Supreme Court stated that “[d]isparate-impact liability mandates the “removal of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers,” not the displacement of valid governmental policies” and that “[g]overnmental or private policies are not contrary to the disparate-impact requirement unless they are “artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers.” Nonetheless, when this was pointed out by parties commenting on the proposal to reinstate the Rule, HUD’s response was that it “declines to add an “artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary” pleading standard or substantive element to the Rule.

The fourth and final claim is that the Rule is not consistent with the Act because, as the Supreme Court stated in the Inclusive Communities decision, the Act should not be used to “second-guess which of two reasonable approaches” an entity should follow, that the Act is not “an instrument to force . . . [defendants] to reorder their priorities,” and that disparate impact liability is properly used only to “remov[e] artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers.” (Citations omitted.) The complaint asserts that the Rule conflicts with these aspects of the decision because (1) it requires defendants to prove that the challenged practice or policy is necessary to achieve a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest and (2) that even if the defendant makes that showing, the plaintiff may prevail by demonstrating that the defendant’s stated interest could be served by some other practice or policy that has a less discriminatory effect. The complaint also notes that in reinstating the Rule, HUD rejected a requirement that the plaintiff’s alternative be “equally effective” or “at least as effective” as the challenged policy in advancing the defendant’s proffered interest.”

The court responded to this claim in part as follows:

“To the extent that the . . . Rule’s “could be served” standard could allow for second-guessing of the type prohibited by Inclusive Communities, NAMIC’s challenge is not the vehicle to decide it. Recall, NAMIC is challenging the Rule in every application to insurers’ underwriting and rating decisions. It is therefore not enough to “point to a hypothetical case in which the [R]ule might lead to an arbitrary result.” (Citations omitted.)

After addressing a specific hypothetical presented by NAMIC, the court then states as follows:

“In sum, the Court cannot conclude, based on a single hypothetical in which the . . . Rule might allow a plaintiff to second-guess an insurer’s priorities, that every underwriting and rating decision will be second-guessed in violation of the [Act]. This is, after all, summary judgment motion, not a law school classroom discussion!”

This aspect of the court’s opinion also is interesting. The court appears to admit that in given situations the Rule may in fact allow a plaintiff to engage in the type of second-guessing of a defendant’s decision-making in a manner that the Supreme Court sought to forestall in the Inclusive Communities decision. As a result, it is not hard to see that another court may find that this means the Rule is inconsistent with that decision.

While it took over 10 years for the issuance of this decision, the case is by no means at an end. NAMIC could elect to appeal the decision to the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Of particular intrigue is whether this case will make it to the Supreme Court. As noted above, the decision in the Inclusive Communities case was 5-4, and the makeup of the Supreme Court has changed significantly since the time of the decision. Should this case reach the Supreme Court, it is not likely that the Court would overrule the decision in Inclusive Communities that disparate impact claims may be brought under the Act. Nevertheless, if the case reaches the Supreme Court, it would provide an opportunity for the Court to establish with more granularity the specific bar that a plaintiff must clear to make a prima facie case of disparate impact under the Act. The earliest that the case could reach the Court is likely 2025, and we don’t know who will be in charge at HUD or the White House then. All we can say is, “stay tuned.”

Alan Kaplinsky Authors American Banker Article on CFPB v. CFSA

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday in CFPB v. CFSA, in which the question presented was whether the CFPB’s funding mechanism violates the Appropriations Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

In an article requested by and published Monday in American Banker’s BankThink, Alan Kaplinsky, Senior Counsel (and former practice group leader) in Ballard Spahr’s Consumer Financial Services Group, argued that the Supreme Court should rule that the CFPB’s funding mechanism is unconstitutional. He did not urge the Court to dismantle the CFPB or invalidate all of its regulations as a remedy. Instead, Alan urged the Court to defer on deciding what the remedy for the constitutional violation should be in order to give Congress an opportunity to subject the CFPB to the annual Congressional appropriations process and ratify most CFPB regulatory and enforcement final actions.

The full article is available here for American Banker subscribers.

On October 17, 2023, from 2:00 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. ET, Ballard Spahr will hold a webinar roundtable, “The U.S. Supreme Court’s Decision in CFSA v. CFPB: Who Will Win and What Does It Mean?” Our exclusive roundtable brings together six attorneys who filed amicus briefs with the Supreme Court in the case. To register, click here.

Barbara S. Mishkin

Respondents File Brief Urging SCOTUS Not to Overrule Chevron

The Secretary of Commerce and the other respondents in Loper Bright Enterprises, et al. v. Raimondo have filed their merits brief in the U.S. Supreme Court urging the Court not to overrule its 1984 decision in Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc. The petitioners filed their merits brief on July 17, 2023 and numerous amicus briefs in support of the petitioners have been filed. The petitioners must file their reply brief by October 16, 2023.

The Chevron decision produced what became known as the “Chevron framework”–the analysis that courts typically invoke when reviewing a federal agency’s interpretation of a statute. Under the Chevron framework, a court will typically use a two-step analysis to determine if it must defer to an agency’s interpretation. In step one, the court looks at whether the statute directly addresses the precise question before the court. If the statute is silent or ambiguous, the court will proceed to step two and determine whether the agency’s interpretation is reasonable. If it determines the interpretation is reasonable, the court will ordinarily defer to the agency’s interpretation.

The petitioners are four companies that participate in the Atlantic herring fishery. The companies filed a lawsuit in federal district court challenging a regulation of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) that requires vessels that participate in the herring fishery to pay the salaries of the federal observers that they are required to carry. The Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) authorizes the NMFS to require fishing vessels to carry federal observers and sets forth three circumstances in which vessels must pay observers’ salaries. Those circumstances did not apply to the Atlantic herring fishery.

Applying Chevron deference, the district court found in favor of NMFS under step one of the Chevron framework, holding that the MSA unambiguously authorizes industry-funded monitoring in the herring fishery. The district court based its conclusion on language in the MSA stating that fishery management plans can require vessels to carry observers and authorizing such plans to include other “necessary and appropriate” provisions. While acknowledging that the MSA expressly addressed industry-funded observers in three circumstances, none of which implicated the herring fishery, the court determined that even if this created an ambiguity in the statutory text, NMFS’s interpretation of the MSA was reasonable under step two of Chevron.

A divided D.C. Circuit, also applying the two-step Chevron framework, affirmed the district court. The majority concluded that under step one of Chevron, the statute was not “wholly unambiguous,” and left “unresolved” the question of whether NMFS can require industry to pay the costs of mandated observers. Applying step two of Chevron, the majority concluded that NMFS’s interpretation of the MSA was a “reasonable” way of resolving the MSA’s “silence” on the cost issue. The dissenting judge concluded that Congress had unambiguously not authorized NMFS to require industry to pay the costs of mandated observers other than in the circumstances specified in the MSA.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to consider the following question:

Whether the Court should overrule Chevron or at least clarify that statutory silence concerning controversial powers expressly but narrowly granted elsewhere in the statute does not constitute an ambiguity requiring deference to the agency.

In their brief, the respondents assert that “overruling Chevron would be a convulsive shock to the legal system” and argue that the Court should not overrule or limit Chevron for the following reasons:

- Chevron respects the unique expertise that federal agencies can bring to bear when adopting gap-filling measures or otherwise resolving a statutory ambiguity.

- Chevron promotes national uniformity in federal law by giving effect to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of a statute and avoiding the potentially conflicting views of the different courts in which review might be sought. Chevron thus reduces the frequency of circuit conflicts and helps to ensure that federal law applies in a uniform manner across the country.

- Regulated parties and the public benefit from the notice and comment rulemaking procedures that agencies, but not courts, can use to interpret federal law. Those procedures give the public greater and less costly opportunities to be heard than piecemeal litigation of the same issues in different courts.

- While the petitioners assert that Chevron represents an unjustified shift in policymaking power from Congress to the Executive, the alternative when a statute is genuinely ambiguous would be to shift policymaking power to the Judiciary. When a court instead upholds an agency’s reasonable interpretation under Chevron, the court respects the policy judgment Congress made in vesting the agency with authority to implement the statute through rulemaking or adjudication.

- The Supreme Court has invoked Chevron to uphold an agency’s reasonable interpretation of a statute at least 70 times. Petitioners would need to identify an extraordinary justification to dispense with that whole line of cases which they fail to provide. All relevant stare decisis considerations weigh against overruling Chevron. First, Chevron is entitled to the strongest form of stare decisis because Congress has legislated against the backdrop of the Chevron framework for 40 years and is free to alter that framework at any time but has declined to do so. Second, overruling Chevron would threaten settled expectations of parties who have relied on agency rules or orders upheld under Chevron. Third, the Chevron framework is workable and sound because it provides a consistent rule of decision that is more likely to yield common ground among judges with diverse perspectives while also respecting the role of the political branches in making federal regulatory policy.

- Petitioners make the fallback argument that if the Court chooses not to discard Chevron entirely, it should at least narrow the doctrine to clarify that it does not apply merely because a statute is silent on a given issue. That clarification would contravene Chevron’s holding that an agency’s interpretation should be reviewed for reasonableness “if the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue.” (emphasis added.) While an agency cannot fill the interstitial silences in a statute except as authorized by Congress, Chevron generally applies only if Congress has authorized the agency to implement the statute through rulemaking or adjudication. Petitioners fail to explain what more Congress must say. They also offer no workable line to distinguish between statutory silence and ambiguity for Chevron purposes.

On September 7, 2023, at the ABA Business Law Section Fall Meeting in Chicago, I moderated a program, “U.S. Supreme Court to Revisit Chevron Deference: What the SCOTUS Decision Could Mean for CFPB, FTC, and Federal Banking Agency Regulations.”

In May 2022, the CFPB issued Circular 2022-3 addressing Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) adverse action notice requirements in connection with credit decisions based on algorithms. The CFPB is now revisiting the issue in Circular 2023-3.

The recent Circular begins with the following question presented: “When using artificial intelligence or complex credit models, may creditors rely on the checklist of reasons provided in CFPB sample forms for adverse action notices even when those sample reasons do not accurately or specifically identify the reasons for the adverse action?”

The following brief response to the question is set forth: “No, creditors may not rely on the checklist of reasons provided in the sample forms (currently codified in Regulation B) to satisfy their obligations under ECOA if those reasons do not specifically and accurately indicate the principal reason(s) for the adverse action. Nor, as a general matter, may creditors rely on overly broad or vague reasons to the extent that they obscure the specific and accurate reasons relied upon.”

The remainder of the Circular is devoted to an analysis of the issue. The ECOA rule, Regulation B, requires that a creditor provide a denied applicant with a “statement of specific reasons for the action taken.” Further, the Regulation B Commentary provides that the “specific reasons disclosed . . . must relate to and accurately describe the factors actually considered or scored by a creditor.”

The CFPB notes that Regulation B includes sample adverse action notices that set forth many of the typical reasons for the denial of credit. The CFPB then advises that:

“As explained in Regulation B, “[i]f the reasons listed on the forms are not the factors actually used, a creditor will not satisfy the notice requirement by simply checking the closest identifiable factor listed.” Rather, the sample forms merely provide an illustrative and non-exclusive list. Thus, if the principal reason(s) a creditor actually relies on is not accurately reflected in the checklist of reasons in the sample forms, it is the duty of the creditor—if it chooses to use the sample forms—to either modify the form or check “other” and include the appropriate explanation, so that the applicant against whom adverse action is taken receives a statement of reasons that is specific and indicates the principal reason(s) for the action taken. Creditors that simply select the closest, but nevertheless inaccurate, identifiable factors from the checklist of sample reasons are not in compliance with the law.” (Footnotes omitted.)

This is a correct observation. A creditor cannot simply select the denial reasons in a sample form that are the closest to the actual denial reasons—the creditor must identify the actual reasons. The CFPB also advises that:

“Specificity is particularly important when creditors utilize complex algorithms. Consumers may not anticipate that certain data gathered outside of their application or credit file and fed into an algorithmic decision-making model may be a principal reason in a credit decision, particularly if the data are not intuitively related to their finances or financial capacity. As noted in the Official Commentary to Regulation B, a creditor must “disclose the actual reasons for denial . . . even if the relationship of that factor to predicting creditworthiness may not be clear to the applicant.” For instance, if a complex algorithm results in a denial of a credit application due to an applicant’s chosen profession, a statement that the applicant had “insufficient projected income” or “income insufficient for amount of credit requested” would likely fail to meet the creditor’s legal obligations.” (Footnote omitted.)

While the CFPB correctly notes the need for a creditor to identify the actual reasons for a decision to deny credit, citing a 1983 case and 1970’s U.S. Senate report, it veers off the rails with the following statement:

“Adverse action notice requirements promote fairness and equal opportunity for consumers engaged in credit transactions, by serving as a tool to prevent and identify discrimination through the requirement that creditors must affirmatively explain their decisions. In addition, such notices provide consumers with a key educational tool allowing them to understand the reasons for a creditor’s action and take steps to improve their credit status or rectify mistakes made by creditors.” (Emphasis added.)

In the second indented paragraph above the CFPB correctly notes the Regulation B Commentary provides that the “creditor must disclose the actual reasons for denial (for example, “age of automobile”) even if the relationship of that factor to predicting creditworthiness may not be clear to the applicant.” The Commentary also provides that a “creditor need not describe how or why a factor adversely affected an applicant. For example, the notice may say “length of residence” rather than “too short a period of residence.” “Thus, Regulation B requires that a creditor disclose the actual reasons for denial. No more, no less. Regulation B does not require the creditor to explain to the consumer how those reasons resulted in a denial of credit.

It also appears as if the CFPB is taking the position that the reasons for a denial decision must be stated with a level of specificity beyond what Regulation B requires. The CFPB observes that:

“Concerns regarding specificity may also arise when creditors take adverse action against consumers with existing credit lines. For example, if a creditor decides to lower the limit on, or close altogether, a consumer’s credit line based on behavioral data, such as the type of establishment at which a consumer shops or the type of goods purchased, it would likely be insufficient for the creditor to simply state “purchasing history” or “disfavored business patronage” as the principal reason for adverse action.”

As one authority for this position, the CFPB cites a 2008 complaint of the Federal Trade Commission against CompuCredit Corporation, which being only a complaint and not a court decision was a deceptive marketing case and not an adverse action case. Further, following the CFPB’s approach, it would appear that a creditor could never use from the model adverse action notice the (1) “Credit application incomplete” denial reason because it does not specify what is missing from the application, or (2) the “Unacceptable type of credit references provided” denial reason because it does not specify what “type” of credit references were unacceptable.

Richard J. Andreano, Jr., John L. Culhane, Jr. & Michael R. Guerrero

In March 2022, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced that it had revised its examination manual to instruct its examiners to apply the “unfairness” standard under the Consumer Financial Protection Act to conduct considered to be discriminatory, whether or not it is covered by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. We first review the changes that the CFPB made to the manual, its rationale for the changes, and how those changes would allow the CFPB to target discrimination more broadly than the circumstances covered by the ECOA. We also review the industry lawsuit challenging the changes, including the reasons asserted for invalidating the changes and the relief sought. We then look at the court decision vacating the changes, including the court’s application of the “major questions” doctrine and the relief granted. We conclude with a discussion of the CFPB’s possible next steps and the decision’s implications for pending CFPB rulemakings and other CFPB actions.

Alan Kaplinsky, Senior Counsel in Ballard Spahr’s Consumer Financial Services Group, leads the conversation, joined by Richard Andreano, a partner in the Group and Practice Leader of the firm’s Mortgage Banking Group.

To listen to the episode, click here.

FinCEN Issues Small Entity Compliance Guide for Corporate Transparency Act

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has published a Small Entity Compliance Guide (the Guide) for beneficial ownership information (“BOI”) reporting under the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), as well as updated FAQs regarding CTA compliance.

The Guide contains six chapters and an appendix. It is 56 pages long. It appears to be useful to its apparent target audience, which is small businesses confronting relatively simple issues under the CTA. The Guide is relatively clear, simply worded and contains helpful infographics. However, what neither the Guide nor the updated FAQs does is provide any real insights into how to interpret the BOI reporting regulations. Rather, they reiterate the existing BOI regulatory requirements. Thus, anyone looking for insights into nuanced CTA issues will be disappointed.

The CTA takes effect on January 1, 2024. On that date, FinCEN needs to have implemented a working data base to accept millions of reports by newly-formed companies required to report BOI under the CTA, as well as reports by the even greater population of existing reporting companies, which must report their BOI by January 1, 2025. This is a logistically daunting task, because FinCEN estimates that over 30 million entities will need to register by the 2025 date. Perhaps one of the most interesting things about the Guidance is that it clearly asserts that the January 1, 2024 date is good, and that the CTA BOI database will be functioning by then.

That claim is debatable. FinCEN still needs to issue important and basic regulations implementing the CTA, including final rules regarding access to the data base, and proposed rules regarding how the existing Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Rule applicable to banks and other financial institutions might be amended – and presumably, expanded – to align with the different and often broader requirements of the CTA. Further, FinCEN’s notice and request for comment regarding FinCEN’s proposed form to collect and report BOI to FinCEN was criticized roundly. Given the backlash, FinCEN now is revising the proposed reporting form.

Similarly, on June 7, 2023, four members of the U.S. House of Representatives (the Chairpersons of the House Committee on Financial Services; the House Committee on Small Business; the House Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions; and the House Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government) sent a letter directed to Janet Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury, and Himamauli Das, Former Acting Director of FinCEN, regarding the status of the implementation of the CTA. The letter, fairly or not, stresses the need for transparency by FinCEN, and implies that January 1, 2024 may not be a viable date.

The fact that FinCEN devoted its limited resources to producing a 56-page publication which repeats but does not explicate current regulatory requirements for BOI reporting is unusual, given FinCEN’s many other pressing demands – such as finishing the rest of the regulations under the CTA. However, it is possible that the Guide is a reaction to demands placed upon FinCEN by certain members of Congress, who are pushing for clarity for affected businesses.

The Guide: Reporting Company

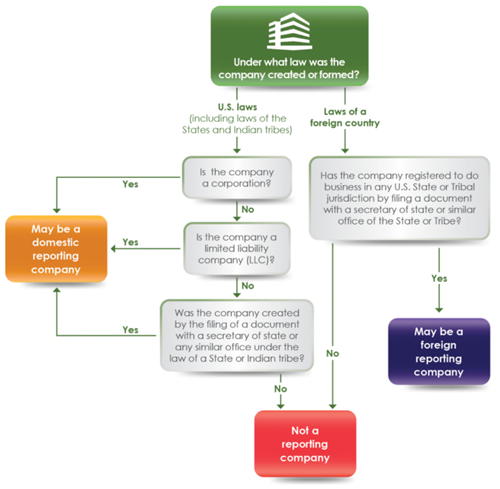

With the above caveats in mind, we now summarize the Guide. As noted, the Guide does not appear to provide additional substantive insight. Rather, it attempts to render existing regulatory requirements more accessible. For example, the Guide includes the following chart regarding the definition of a “reporting company” required to comply with the CTA:

The nuanced question to which this seemingly simple chart references, but does not expand upon, is precisely when an entity “may” be a reporting company covered by the CTA. However, the Guidance later provides a relatively useful set of questions for entities to consider as to whether they qualify as one of the 23 entities which the CTA explicitly exempts from its coverage.

The Guide: Substantial Control

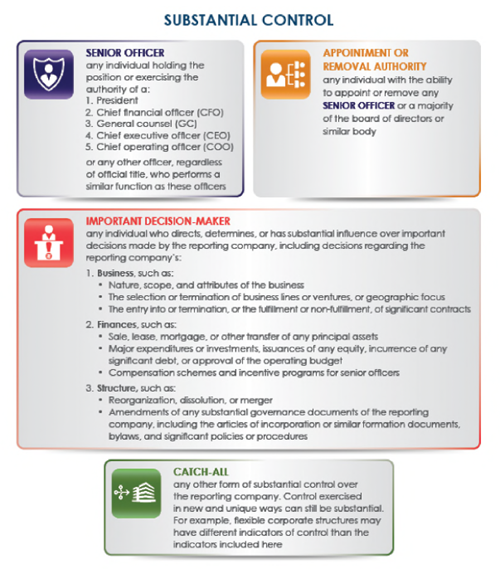

The Guide also offers the following graphic regarding the issue of “substantial control“ under the CTA. This is one of the thorniest issues under the CTA, given the incredible breadth of the term.

Many notable commentators have bemoaned the breadth of the vague “substantial control” prong under the CTA, in contrast to the CDD Rule, which requires entities to identify only a single “control person.” For example, Jim Richards has suggested, satirically, that his favorite bartender could qualify under the CTA as a beneficial owner of his AML consulting company, given his “substantial influence” over “important decisions” being made by Mr. Richards.

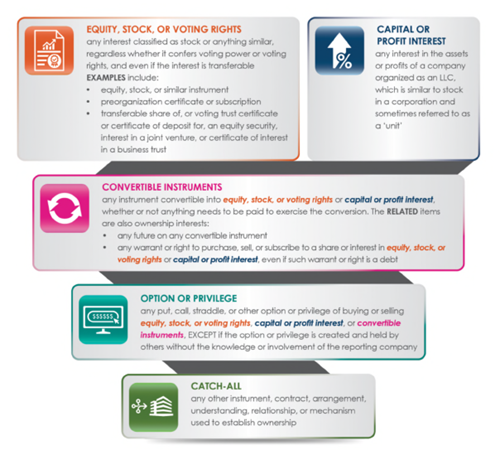

The Guide: Ownership

Similarly, the Guide provides this graphic regarding the “ownership” prong of beneficial ownership. Although the ownership interest is cabined concretely to a 25% interest, similar to the CDD Rule, the below graphic illustrates how expansively such interests may be considered:

Similar to the issue of companies exempted from the definition of reporting companies, the Guide also contains a series of yes-or-no questions regarding ownership interests under the CTA.

The FAQs

FinCEN has updated its FAQs on the CTA, first published in March 2023. Unfortunately, like the Guide, the updated FAQs provide no additional analysis, but rather regurgitate the existing CTA regulatory requirements. They note that the regulations regarding access to the CTA database are still forthcoming, and that FinCEN is still revising the actual CTA reporting form. The FAQs do not mention the regulations regarding alignment with the CDD Rule which FinCEN still needs to propose.

Having said that, FAQ D.6 is notable for certain professionals. It asks, “Is my accountant or lawyer considered a beneficial owner?” Here is the answer, which echoes language from the federal register regarding the final rule:

Accountants and lawyers generally do not qualify as beneficial owners, but that may depend on the work being performed.

Accountants and lawyers who provide general accounting or legal services are not considered beneficial owners because ordinary, arms-length advisory or other third-party professional services to a reporting company are not considered to be “substantial control” (see Question D.2). In addition, a lawyer or accountant who is designated as an agent of the reporting company may quality for the “nominee, intermediary, custodian, or agent” exception from the beneficial owner definition.

However, an individual who holds the position of general counsel in a reporting company is a “senior officer” of that company and is therefore a beneficial owner. FinCEN’s Small Entity Compliance Guide includes a checklist to help determine whether an individual qualifies for an exception.

Likewise, FAQ E.3 asks, “Is my accountant or lawyer considered a company applicant?” Again, the below language echoes verbiage from the federal register:

An accountant or lawyer could be a company applicant, depending on their role in filing the document that creates or registers a reporting company. In many cases, company applicants may work for a business formation service or law firm.

An accountant or lawyer may be a company applicant if they directly filed the document that created or registered the reporting company. If more than one person is involved in the filing of the creation or registration document, an accountant or lawyer may be a company applicant if they are primarily responsible for directing or controlling the filing.

For example, an attorney at a law firm that offers business formation services may be primarily responsible for overseeing preparation and filing of a reporting company’s incorporation documents. A paralegal at the law firm may directly file the incorporation documents at the attorney’s request. Under those circumstances, the attorney and the paralegal are both company applicants for the reporting company.

The FAQ E.3 response re-emphasizes how the CTA can pull lawyers and other professionals directly into its reporting requirements, even if they are not beneficial owners themselves.

Peter D. Hardy, Scott Diamond, Siana Danch & Kaley Schafer

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has issued a flurry of publications relating to the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA). They pertain, in part, to a proposed extension of the filing deadline for certain reports of Beneficial Ownership Information (“BOI”); a proposed revision to the BOI reporting form; and expanded FAQs. We discuss each in turn.

First, on September 28, 2023, FinCEN proposed a rule to extend the filing deadline for reports of BOI by entities created or registered on or after the CTA’s effective date of January 1, 2024. Specifically, the proposed rule would extend the filing deadline from 30 to 90 days for both domestic and foreign entities created or registered on or after January 1, 2024 and before January 1, 2025. Written comments to this proposed rule are due on October 30, 2023. The 30-day filing deadline for pre-existing entities, which must file BOI reports by January 1, 2025, would not be affected by this proposed rule.

FinCEN has explained in the Federal Register that this extension “will provide new reporting companies additional time to obtain the information necessary to complete their initial BOI reports[,]” and “will give reporting companies more time to resolve questions that may arise in the process of completing their initial BOI reports.” This proposed delay is not very surprising. FinCEN has been criticized regarding its slow roll-out of the CTA regulations and any guidance, given the looming January 1, 2024 effective date – including by members of Congress, who pressed FinCEN in June 2023 for more public clarity on exactly how the CTA will apply.

Second, on September 29, 2023, FinCEN proposed a revised BOI reporting form. Written comments are due October 30, 2023. As FinCEN acknowledges in the Federal Register, the previously proposed BOI reporting form was roundly criticized:

Notably, commentators were uniformly critical of the checkboxes that would allow a reporting company to indicate if certain information about a beneficial owner or company applicant is “unknown,” or if the reporting company is unable to identify information about a beneficial owner or company applicant….

A significant number of these comments expressed concern that the checkboxes would incorrectly suggest to filers that it is optional to report required information, and that reporting companies need not conduct a diligent inquiry to comply with their reporting obligations. These commentators requested that FinCEN remove such checkboxes.

Accordingly, the revised form has deleted the checkboxes, and every field must be completed in order to submit the form. Nonetheless, due to difficulties that reporting companies may face in promptly obtaining all required information, FinCEN indicated that the reporting form may change again, based on feedback once the CTA becomes effective. Specifically, FinCEN has suggested that there may be a mechanism for filers to temporarily indicate, via a dropdown menu, that they are unable to provide certain information for certain reasons, such as “Cannot Contact BO.” Such forms would be accepted into the BOI database but still would be deemed to be incomplete and non-compliant. FinCEN states that the benefits of this approach would be to:

(1) provide a mechanism for the collection of some beneficial ownership information that would be of immediate use to law enforcement agencies and other authorized users of BOI; (2) provide insight into any common difficulties that might arise so that FinCEN can potentially provide guidance, frequently asked questions (FAQs), or follow-up with reporting companies or beneficial owners; and (3) provide notice for FinCEN that an incomplete report has been submitted and facilitate appropriate related follow-up.

Importantly, “[F]orms will only be considered complete and compliant once the missing information is subsequently added, the drop down option is removed from each field, and the form is updated.” This leaves open the questions of how long does a filer have to bring the form into compliance and the effect of a reporter simply being unable to provide information despite reasonable efforts.

In this Federal Register publication, FinCEN also provides some updated estimates regarding BOI reporting. FinCEN estimates that 32,556,292 entities will file initial BOI reports in Year 1 (2024), and that 4,998,468 initial BOI reports will be filed annually in Year 2 (2025) and beyond. The total five-year average of expected initial BOI reports is 10,510,160. FinCEN also estimates that 6,578,732 updated BOI reports will be filed in Year 1, and that 4,456,452 updated BOI reports will be filed annually in Year 2 and beyond. The total five-year average of expected updated BOI reports is 12,880,908. FinCEN estimates that the total costs in Year 1 of initial BOI reports will be $21.7 billion. FinCEN further estimates that the total annual costs of initial BOI reports in Year 2 and onward will be $3.3 billion. For updated BOI reports, FinCEN estimates that the total costs will be $1 billion in Year 1, and will be $2.3 billion in Year 2 and onward.

Third, on September 29, 2023, FinCEN published a request for comment on the information that FinCEN proposes to collect for those seeking a FinCEN identifier, which can be used as a substitute for providing other identification information under the CTA. FinCEN has explained that a FinCEN identifier can provide administrative efficiency for individuals likely to be identified as a BO for multiple reporting companies, and data security for individuals who perceive less risk in providing their personal identifiable information indirectly to FinCEN, through reporting companies. The proposed information necessary to apply for a FinCEN identifier, set forth in the Appendix of the request for comment, includes the applicant’s name, address, date of birth and official form of documentation, such as a state-issued driver’s license or a U.S. passport, all provided under a certification of accuracy and completeness. Written comments are due on October 30, 2023.

Fourth, on September 29, 2023, FinCEN expanded the FAQs pertaining to the CTA. The expanded FAQs were accompanied by a four-page brochure regarding BOI reporting, and was preceded shortly by FinCEN’s September 18, 2023 publication of a Small Entity Compliance Guide for the CTA. The new FAQs, many of which pertain to FinCEN identifiers, provide:

- What information should a reporting company report about a beneficial owner who holds their ownership interests in the reporting company through multiple exempt entities? [If a beneficial owner owns or controls their ownership interests in a reporting company exclusively through multiple exempt entities, then the names of all of those exempt entities may be reported to FinCEN instead of the individual beneficial owner’s information.]

- Is an unaffiliated company that provides a service to the reporting company by managing its day-to-day operations, but does not make decisions on important matters, a beneficial owner of the reporting company? [The unaffiliated company itself cannot be a beneficial owner of the reporting company because a beneficial owner must be an individual.]

- Is a member of a reporting company’s board of directors always a beneficial owner of the reporting company? [No.]

- Can a parent company file a single BOI report on behalf of its group of companies? [No]

- What should I do if I learn of an inaccuracy in a report? [If a beneficial ownership information report is inaccurate, your company must correct it no later than 30 days after the date your company became aware of the inaccuracy or had reason to know of it. This includes any inaccuracy in the required information provided about your company, its beneficial owners, or its company applicants.]

- Can a third-party service provider assist reporting companies by submitting required information to FinCEN on their behalf? [Yes.]

- What is a FinCEN identifier? [A “FinCEN identifier” is a unique identifying number that FinCEN will issue to an individual or reporting company upon request after the individual or reporting company provides certain information to FinCEN.]

- How can I use a FinCEN identifier? [When an individual who is a beneficial owner or company applicant has obtained a FinCEN identifier, reporting companies may report the FinCEN identifier of that individual in the place of that individual’s otherwise required personal information on a beneficial ownership information report.]

- How do I request a FinCEN identifier? [Individuals will be able to request a FinCEN identifier on or after January 1, 2024, by completing an electronic web form. The FAQ response provides more detail].

- Are FinCEN identifiers required? [No.]

- Do I need to update or correct the information I submitted to obtain a FinCEN identifier? [Yes. Individuals must update or correct information through the FinCEN identifier application that is also used to request a FinCEN identifier.]

- Is there any way to deactivate an individual’s FinCEN identifier that is no longer in use so that the individual no longer has to update the information associated with it? [FinCEN is actively assessing options to allow individuals to deactivate a FinCEN identifier so that they do not need to update the underlying personal information on an ongoing basis.]

Fifth, on September 14, 2023, FinCEN published a proposed rule that BOI received through the CTA is exempt from the Federal Privacy Act of 1974 (“Privacy Act”), unless stated explicitly otherwise in the CTA and its implementing regulations. Very generally, the Privacy Act, subject to various exemptions, protects records about individuals retrieved by personal identifiers such as a name, social security number, or other identifying number or symbol. The comment period closes on October 16, 2023.

Finally, FinCEN still needs to issue a final rule regarding access to BOI. In a filing with the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (“OIRA”), FinCEN had indicated that it would promulgate this final rule by September 2023, which has come and gone. FinCEN also still needs to issue a proposed rule regarding revisions to the Customer Due Diligence (“CDD”) Rule (which requires financial institutions (“FIs”) to obtain BOI from defined entity customers) to align it with the CTA regulations; this proposed rule and its attendant changes could have major implications for FIs, which have been operating for years with specific systems to comply with the CDD Rule. FinCEN has indicated in another OIRA filing that it would promulgate this proposed rule by November 2023. Even if FinCEN complies with this self-imposed deadline, a final rule aligning the CDD Rule with the CTA – which could be complicated – clearly will not be in place until several months after the CTA becomes effective on January 1, 2024.

Peter D. Hardy, Scott Diamond, Siana Danch & Kaley Schafer

CFPB Launches FCRA Rulemaking to Eliminate Creditor Use of Medical Debt

On September 21, 2023, with limited time to digest the comments received by September 11, 2023 from the request for information regarding medical payment products, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) started the FCRA rulemaking process. The press release describes a “rulemaking process to remove medical bills from Americans’ credit reports.” However, the proposed rulemaking includes changes to critical definitions and processes under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which should not be overlooked. The rulemaking was announced by CFPB Director Rohit Chopra at a press call on medical debt hosted by Vice President Kamala Harris. Vice President Harris’ prepared remarks claimed the rulemaking “will improve the credit scores of millions of Americans so that they will better be able to invest in their future.” Citing concerns about the accuracy of medical debt billing and reporting practices, Director Chopra’s prepared remarks claimed that “research has found medical billing history has limited predictive value in underwriting.” Chopra also cited to the CFPB Bulletin 2022-01: Medical Debt Collection and Consumer Reporting Requirements in Connection with the No Surprises Act and changes made by credit reporting agencies (CRAs) earlier this year to exclude certain medical debt from consumer reports. To conclude his remarks, Director Chopra noted that “the proposals we are outlining today would ensure that credit decisions are based on someone’s ability to repay a debt, not their ability to file disputes and navigate red tape.”

The CFPB’s outline of the FCRA rulemaking includes the following proposals for consideration and comment:

- Change key defined terms: Consumer Reporting Agency, Consumer Report, Assembling or Evaluating

- Clarify applicability of FCRA to data brokers and prohibit the sale of covered data for purposes other than those authorized under the FCRA

- Clarify prohibited marketing and advertising purposes

- Clarify the interpretation of permissible purposes to furnish a consumer report in response to a consumer request and legitimate business need

- Clarify that furnishing credit header data is considered a consumer report

- Address CRA’s obligation to protect consumer reports from unauthorized access

- Change the processes to dispute the accuracy of a consumer report for (1) those that are classified by a consumer reporting agency or furnisher as involving legal matters and (2) those involving systemic issues at a consumer reporting agency or furnisher

- With respect to medical debt tradelines, (1) revise Regulation V § 1022.30(d) to prohibit creditors from obtaining or using medical debt collection information to determine a consumers’ credit eligibility and (2) prohibit consumer reporting agencies from including medical debt collection tradelines on consumer reports furnished for such purposes

- Consider the appropriate implementation period

Notably, the FCRA Rulemaking Outline acknowledges the applicability of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (SBREFA) requiring the CFPB to consider the economic impact that rule will have on small entities, which requirement was largely ignored with the credit card late fee rulemaking earlier this year. The CFPB also created a Discussion Guide: Consumer Reporting Rule SBREFA Outline to aid the CFPB in obtaining feedback from the small entities that will be directly affected by the proposed regulations.

We have previously blogged about the CFPB’s plans to regulate data brokers and credit header information under FCRA and the Second Circuit’s ruling that FCRA does not contemplate a threshold inquiry by the court as to whether an alleged inaccuracy is “legal” for purposes of determining whether the plaintiff has stated a cognizable claim under the FCRA.

We are curious to see the approach the CFPB will take with respect to defined terms for its rulemaking. While the CFPB is authorized to implement FCRA through rulemaking under Regulation V, only Congress may revise defined terms under FCRA. The CFPB was reminded of its function when it unsuccessfully tried to expand the definition of applicant under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which was struck down in the Townstone Mortgage case. The CFPB has appealed the adverse decision to the Seventh Circuit.

We will continue to monitor any developments with this FCRA rulemaking, including any comments to the proposal or additional analysis that may be performed as a result of the comments submitted and concerns expressed about the proposal.

Kristen E. Larson, John L. Culhane, Jr. & Reid F. Herlihy

CFPB Releases Updated 1071 Small Business Lending FAQs

On September 14, 2023, the CFPB released Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding the Small Business Data Collection Rule (the Rule). These FAQs are in addition to the set published in June 2023, which are dated. Some, but not all, of the FAQs are discussed below.

Covered Credit Transactions

A few of the updated FAQs relate to the definition of a “covered credit transaction,” which includes the following topics:

- Consumer-designated credit: The FAQs reiterate that consumer-designated credit is excluded from the Rule, even if the proceeds are used for business or agricultural purposes, as long as the credit is offered or extended primarily for personal, family or household purposes.

- Letters of credit: The CFPB reiterates that letters of credit are excluded from coverage of the Rule. The FAQ defines a letter of credit as an instrument issued by a bank that promises, upon the presentation of certain documents and/or satisfaction of certain conditions, to direct payment to a beneficiary of the instrument. Letters of credit are not extensions of credit. However, if the letter of credit results in an extension of credit, then that extension may be a covered transaction.

- Participation loans: A participation loan is generally a covered credit transaction. The purchase of a partial interest in a credit transaction through a loan participation agreement is not considered a covered credit transaction. However, if the lead lender is the only financial institution needed to make a credit decision to originate the loan, or the lead lender is the last financial institution with authority to set material terms of the loan, then the lead lender would count the loan as a covered credit transaction (assuming the criteria for coverage are met).

- Trade credit exclusion and application to loans for goods/services from a retailer: An extension of credit by a financial institution, other than the supplier, the proceeds of which will be used to purchase goods or services from a retailer is not considered trade credit. Trade credit, which is excluded from the definition of a covered credit transaction, is a financing arrangement wherein a business acquires goods or services from another business without making immediate payment in full to the business providing the goods or services.

Small Business

- The CFPB clarified that an individual’s personal income is not considered when calculating a sole proprietorship’s gross annual revenue, because it is not revenue earned by the for-profit business applying for a covered credit transaction.

- The CFPB clarified that a guarantor’s revenue is excluded from determining whether a borrower is a small business. As a reminder, the definition of an applicant does not include other persons who are or may become contractually liable regarding an extension of business credit, such as guarantors, sureties, or endorsers.

Record Retention

The updated FAQs include a new section regarding record retention requirements, which covers:

- General record retention requirements: The CFPB reiterates that there are two primary record retention requirements. First, a covered financial institution must retain evidence of compliance the Rule, including a copy of its small business lending application register (LAR), for at least three years after submitting it to the CFPB. Second, a covered financial institution must maintain the demographic information collected pursuant to the Rule separate from the rest of the application and accompanying information.

- Record retention requirements if a covered financial institution relies on the exception to the firewall prohibition: A covered financial institution must still maintain demographic information collected pursuant to the Rule (and separately from the rest of the application), even if the financial institution relies on the exception to the firewall provision. The FAQs clarify that the exception to the firewall prohibition does not extend to the record retention requirements.

Firewall

The CFPB added a new section to discuss the rule’s requirement to shield demographic information from employees involved in decision-making, known as the “firewall” provision. This section offers the following information, among other items, regarding the firewall:

- Determining whether to establish a firewall: If covered financial institution determines that an employee involved in decision-making should have access to the demographic information in order to fulfill his or her job duties, it means it is not feasible to establish and maintain the firewall as to that employee. The covered financial institution is not required to perform a separate analysis of the feasibility of establishing or maintaining a firewall. It is only required to determine whether the employees and officers who are involved in making determinations concerning covered applications should have access to protected demographic information. A determination that one employee or officer (or one group of employees or officers) should have access to demographic information protected by the firewall does not mean that it is not feasible to establish and maintain the firewall for other employees who are involved in decision-making.

- Complying with the rule when a covered financial institution determines it cannot maintain a firewall: The rule allows a covered financial institution to meet an exception to the firewall rule if it determines that it is not feasible to maintain a firewall with regard to an employee or a group of employees. In order to meet the exception in the rule, the financial institution must determine which employees make decisions on covered applications, then determine which of those employees should have access to protected demographic information to fulfil other job duties. A covered financial institution may make this determination on an individual-by-individual basis, or it may determine that a group of employees or officers with the same job description or assigned duties should have access for purposes of the exception. For example, there may be one employee or a group of employees who make decisions on covered applications, and also have other job duties, such as preparing reports, for which they should have access to protected demographic information. The financial institution is then required to establish a firewall with respect to the employees who do not need to access protected demographic information, and provide the required notice to applicants. The required notice can be sent to specific applicants or a broad group of applicants depending on the circumstances.

- Covered financial institutions may use current systems or processes for determining which employees should have access to data: A covered financial institution may use any lawful factors to determine whether an employee should have access to demographic information collected from applicants. For example, a covered financial institution may consider its size, the number of employees and officers within the relevant line of business or at a particular branch or office location, the number of covered applications the covered financial institution has received or expects to receive, and its current or reasonably anticipated staffing levels, operations, systems, processes, policies, and procedures. A covered financial institution is not required to change its systems or processes for the sole purpose of determining which employees and officers should have access.

- Access of employees and officers to the data after final action on the application is taken: An employee or officer who is involved in making a determination concerning a covered application may not have access to the applicant’s protected demographic information after the final action is taken on that applicant’s covered application.

- Documentation evidencing a firewall: The firewall provision does not include any specific documentation requirements. However, a covered financial institution is generally required to retain evidence of compliance with the rule for three years. Documentation evidencing compliance with the firewall provision may include items such as job descriptions or procedures that support the financial institution’s determinations of who should have access to demographic data.

Loran Kilson & Kaley Schafer

CFPB Releases 2022 Mortgage Market Activity and Trends Report

The CFPB recently released a report entitled Data Point: 2022 Mortgage Market Activity and Trends based on 2022 data reported by lenders under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA).

The CFPB addresses various 2022 lending results, with many results reflecting changes from 2021 to 2022 based on increases in mortgage interest rates and other economic factors. Among other points, the CFPB notes that:

- The total number of mortgage loan applications decreased from approximately 23.3 million in 2021 to approximately 14.3 million in 2022, a decrease of approximately 38.6%.

- The total number of mortgage loan originations decreased from approximately 15.0 million in 2021 to approximately 8.4 million in 2022, a decrease of approximately 44.1%.

- With closed-end, site-built single-family mortgage originations, the total number of purchase money loans decreased from approximately 5.1 million in 2021 to approximately 4.1 million in 2022 (approximately a 19.5% decrease), and the total number of refinance loans decreased from approximately 8.3 million in 2021 to approximately 2.2 million in 2022 (approximately a 73.2% decrease).

- Most of the refinance loans were cash-out refinance loans. (This makes sense based on a number of factors. The rise in interest rates significantly reduced refinance loans intended to obtain better loan terms. The increase in home prices created equity that homeowners could tap into. Inflationary and other economic pressures created a need for cash.)

- Home equity line of credit (HELOC) originations increased from approximately 962,000 in 2021 to approximately 1.4 million in 2022, an increase of approximately 41.2%.

- The CFPB notes that one factor likely contributing to the increase was that for 2021 a temporary HELOC reporting threshold of at least 500 originations in each of the prior two calendar years was still in place, and for 2022 the permanent threshold of at least 200 originations in each of the prior two calendar years became effective. The number of institutions reporting HELOC originations increased from 936 in 2021 to 1,150 in 2022.

- The CFPB observes that the “change in reporting threshold alone, however, cannot explain all of the increase in HELOC origination volume.” The CFPB surmises that the increase in HELOC originations also is most likely “due to some consumers resorting to HELOCs instead of cash-out refinance loans to extract home equity in a high interest rate environment.”

- The median total loan costs for home purchase loans increased from $4,889 in 2021 to $5,954 in 2022, an increase of 21.8%. The CFPB advises that this “represents the largest annual increase of total loan costs since this information was first collected in the HMDA data in 2018.” The median total loan costs for refinance loans increased from $3,336 in 2021 to $4,979 in 2022, an increase of 49.3%. The CFPB notes that Black and Hispanic White borrowers experienced higher increases in median total loan costs in 2022 compared to 2021 than Asian and Non-Hispanic white borrowers. The CFPB notes that it “believe[s] that this is the first time that a sharp rise in total loan costs that borrowers had to pay upfront is documented.”

- It appears that the payment of discount points by borrowers was a significant factor contributing to the increase in total loan costs. The CFPB advises that a higher percentage of borrowers reported paying discount points in 2022 than any other years since 2018, when discount points were first reported with HMDA data. The CFPB surmises that the increase in the percentage of “borrowers paying discount points could be due to the higher interest rate environment incentivizing borrowers to buy down the interest rate that would have been otherwise regarded as too high.”

- With first lien closed-end home purchase loans secured by single-family principal residences and not for commercial/business purpose, the percentage of loans with discount points in 2022 was approximately 50.2%, compared to approximately 29.2%, 31.4%, 32.7% and 32.1% of home purchase loans in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively. In dollars, the median discount point amount was approximately $2,370 in 2022, compared to $1,054, $1,098, $1,252, and $1,225 in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively.

- With first lien closed-end refinance loans secured by single-family principal residences and not for commercial/business purpose, the percentage of loans with discount points in 2022 was approximately 60.8%, compared to approximately 44.3%, 38.2%, 38.1%, and 40.9% of refinance loans in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively. In dollars, the median discount point amount was approximately $2,878 in 2022, compared to $1,690, $1,782, $1,667, and $1,619 in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively.

- Another factor that may have contributed to the increase in loan costs was that when rates are low, often the borrower will opt for an above market rate in return for the lender not imposing various closing costs. In higher rate environments, borrowers have a greater incentive to pay closing costs in return for a lower rate.

- The median loan amount for home purchase loans in 2022 was approximately $295,000 for non-Hispanic White borrowers, $297,000 for Black borrowers, $300,000 for Hispanic White borrowers, and $449,000 for Asian borrowers. The CFPB notes for the first time since 2018 the median loan amount of home purchase loans for non-Hispanic White borrowers ranked below the median loan amounts of Black and Hispanic White borrowers.

- The median loan amount for refinance loans in 2022 was approximately $216,000 for Black borrowers, $220,000 for non-Hispanic White borrowers, $238,000 for Hispanic White borrowers, and $370,000 for Asian borrowers.

- The median credit scores for home purchase loans in 2022 were 695 for Black borrowers, 718 for Hispanic White borrowers, 751 for Asian borrowers and 762 for non-Hispanic White borrowers.

- For home purchase applications, the overall denial rate increased from 8.3% in 2021 to 9.1% in 2022. For refinance applications, the overall denial rate increased from 14.2% in 2021 to 24.7% in 2022.

- For home purchase applications, in 2022 the denial rates were 16.8% for Black applicants, 12.0% for Hispanic White applicants, 9.6% for Asian applicants, and 6.7% for non-Hispanic White applicants. The corresponding denial rates in 2021 were 15.7%, 9.7%, 7.9%, and 6.3%, respectively.

- For refinance applications, in 2022 the denial rates were 35.8% for Black applicants, 27.6% for Hispanic White applicants, 22.9% for Asian applicants, and 20.2% for non-Hispanic White applicants. The corresponding denial rates in 2021 were 23.6%, 17.6%, 12.3%, and 11.8%, respectively.

In a press release announcing the Report, the CFPB noted that “[o]verall affordability declined significantly, with borrowers spending more of their income on mortgage payments and lenders more often denying applications for insufficient income.”

In a separate statement, CFPB Director Rohit Chopra stated: