In This Issue:

- Kentucky Federal District Court Issues Order Enjoining the CFPB From Enforcing the Small Business Data Collection Rule as to All Companies Affected by the Rule

- CFPB Files Opposition to Preliminary Injunction Motion of Plaintiffs in Kentucky Lawsuit Challenging CFPB’s Small Business Lending Rule

- The Dilemma Facing Lenders Subject to the 1071 Small Business Data Collection and Reporting Rule

- Farm Credit Trade Associations File Motion Seeking to Intervene in Texas Lawsuit Challenging CFPB Small Business Lending Rule

- Is There a Better Route to Nationwide Relief Than Multiple Preliminary Injunction Motions in the Texas Lawsuit Challenging the CFPB Small Business Lending Rule?

- Texas Federal District Court Invalidates CFPB Exam Manual Changes Which Opined That Discrimination Is a UDAAP Violation

- Rationale for Federal District Court Issuing an Injunction in Addition to Vacating Changes to UDAAP Exam Manual

- This Week’s Podcast Episode: Responding to Direct and Indirect Identity Theft Disputes Under the FCRA: What Are the Differences?

- CPPA Publishes New Draft Regulations Addressing AI, Risk Assessments, Cyber Audits

- CFPB Annual CARD Act, HOEPA, QM Adjustments Do Not Include Credit Card Penalty Fees Safe Harbors

- Amendments to Ohio’s Administrative Rules Relating to Residential Mortgage Lending

- Report on the ABA Committee on Consumer Financial Services Program Regarding the Supreme Court Case Poised to Eliminate Chevron Judicial Deference Framework

- CFPB Highlights Applicable HUD-Issued RESPA Guidance

- CFPB Director Rohit Chopra Addresses Mortgage Post-Crisis Reforms and Importance of Consumer Protection Regulations

- Did You Know?

On September 14th, the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky granted the plaintiff’s motion to preliminarily enjoin the CFPB from implementing the Small Business Lending Rule (Rule) promulgated under section 1071 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act. As a reminder, the plaintiffs in the Kentucky lawsuit are the Kentucky Bankers Association and several Kentucky banks. Importantly, the order does not limit the beneficiaries of the injunctive relief to just the named plaintiffs and their members as happened in the earlier case challenging the 1071 Rule brought by the American Bankers Association, Texas Bankers Association in Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. In the Texas case, the court stipulated that the only beneficiaries of the preliminary injunction would be the members of the plaintiff’s trade associations (American Bankers Association and Texas Bankers Association). As a result of the Texas court limiting the beneficiaries of the injunction to just the plaintiffs trade associations, several other trade associations intervened in the Texas lawsuit and filed motions for preliminary injunctions which are still pending before the court.

The Kentucky opinion is welcome news for those financial institutions who were not members of the American Bankers Association or Texas Bankers Association and, therefore could not avail themselves of the relief granted by the Texas court. This order places all financial institutions on an equal footing and should moot all pending motions in the Texas court (and the flurry of motions to intervene in the Texas case).

The CFPB is enjoined from enforcing the Rule until the Supreme Court issues an opinion in the case regarding the agency’s constitutionality. The Kentucky opinion differs from the Texas case in that the Texas court enjoined the CFPB from implementing and enforcing the Rule until the Supreme Court reverses the decision in Cmty. Fin. Servs. Ass’n of Am., Ltd. v. CFPB, a trial on the merits of the action, or until further order from the Texas court. The Kentucky opinion does not indicate that any further action from the Court may be taken. The Court could make the injunctive relief coterminous with the Texas injunction; however, that would require another court order. As another reminder, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case challenging the funding mechanism of the CFPB as being unconstitutional on October 3, 2023. The Court granted the motion for preliminary injunctive relief for the following reasons:

- Given the circuit split regarding the CFPB’s constitutionality, the likelihood of success on the merits is uncertain at this time. Therefore, this did not “tip the scale in either direction” with regard to whether a preliminary injunction should be issued.

- The plaintiffs have suffered irreparable harm in that the compliance costs incurred in preparation for complying with the Rule are unlikely recoverable even in the event the Supreme Court holds the CFPB’s funding structure is unconstitutional.

- The CFPB will not suffer any harm from the injunction, as they are not able to enforce the Rule until October 2024 (which is the initial compliance date for small business lenders with higher volumes of lending). Moreover, the CFPB will not lose any benefit with the issuance of the injunction. The court noted that because “the Supreme Court’s decision will be issued by June 2024 at the latest, the CFPB will suffer no harm and the public will not lose any benefit by the issuance of the preliminary injunction.”

While we believe that there is no longer any need for the Texas Court to rule on any motions for injunctive relief, before popping the cork on the champagne we must await the CFPB’s reaction to the Kentucky opinion and whether the Court agrees with us that all pending motions in the Texas case are now moot. Stay tuned!

Kaley Schafer, Richard J. Andreano, Jr. & Alan S. Kaplinsky

The CFPB has filed its opposition to the motion for a preliminary injunction filed by the plaintiffs in the Kentucky federal court lawsuit challenging the CFPB’s final small business lending rule (Rule).

The plaintiffs in the Kentucky lawsuit are the Kentucky Bankers Association and several Kentucky banks. The Kentucky plaintiffs chose to file a separate lawsuit rather than intervene in the lawsuit pending in a Texas federal district court challenging the Rule filed by the American Bankers Association, Texas Bankers Association, and Rio Grande Bank and in which several credit unions, community banks, credit union and community bank trade associations, an auto floor plan lender, and a trade association for financial services companies and manufacturers in the equipment finance sector have already intervened and filed preliminary injunction motions. The CFPB has filed its opposition to the preliminary injunction motion filed by the credit union and community bank intervenors and presumably will also oppose the preliminary injunction motion filed by the floor plan lender and equipment finance trade association.

In its opposition to the preliminary injunction motion filed by the Kentucky plaintiffs, the CFPB makes the following principal arguments:

- The Kentucky plaintiffs are not likely to succeed on the merits of their constitutional challenge because the CFPB’s funding mechanism does not violate the Appropriations Clause and have waived any argument that the Rule violates the Administrative Procedure Act because they have failed to adequately explain the basis for their argument.

- The Kentucky plaintiffs have not provided specific evidence establishing a likelihood of imminent harm without preliminary relief. As to the plaintiff banks, it is not clear that all of them will even be subject to the Rule—at least at any point in the imminent future. The banks’ argument that, in addition to unrecoverable compliance costs, they will suffer irreparable harm in the form of a competitive disadvantage because the Texas federal court has granted relief to ABA members that are located or do business in Kentucky is too abstract and lacking in specifics to warrant an injunction. With respect to the KBA, it has not identified any particular member bank that it believes is facing irreparable harm or identify specific costs that a member bank is incurring. It also has not identified any specific harm that the KBA itself is suffering or any specific costs that it is incurring.

- The balance of equities weighs against preliminary relief because it will harm the public interest by delaying a congressionally mandated Rule that will produce significant benefits for small businesses.

We continue to see the CFPB’s current litigation strategy of opposing nationwide preliminary injunctive relief as a waste of the parties’ and the courts’ time and resources, particularly when the CFPB can quickly and efficiently remedy this chaotic situation by issuing a proposal to delay the Rule’s tiered compliance dates.

Richard J. Andreano, Jr., John L. Culhane, Jr., Michael Gordon & Alan S. Kaplinsky

The Dilemma Facing Lenders Subject to the 1071 Small Business Data Collection and Reporting Rule

We recently reported that a federal district court in Kentucky enjoined the CFPB from implementing the small business data collection and reporting rule, also referred to as the 1071 rule based on the Dodd-Frank section requiring the rule (the “Rule”). Unlike a similar injunction against the rule issued by a federal district court in Texas, the preliminary injunction issued by the Kentucky court is not limited to the members of the plaintiff trade associations and the plaintiff banks. As we have reported, the limitation of the Texas court preliminary injunction to the members of the plaintiff trade associations and plaintiff bank has resulted in other trade associations seeking to intervene in the case in order to expand the scope of the injunction to their members. You can find more on this here, here, and here.

However, unlike the Texas court order, the order by the Kentucky court does not expressly provide for a delay of the implementation dates under the Rule for the period that the stay is in effect. The order of the Kentucky court simply enjoins the CFPB from enforcing the Rule “until the Supreme Court issues an opinion ruling that the funding structure of the CFPB is constitutional.” Thus, without subsequent action by a court, Congress or even of the CFPB, lenders not covered by the Texas court order may not receive any relief from the implementation dates of the Rule if the Supreme Court finds the funding structure of the CFPB to be constitutional. Additionally, even though lenders covered by the Texas court order will benefit from a delay in the implementation dates for the period of time that the stay is in effect, the first two implementation dates are not reasonable in the first place. Thus, lenders subject to the Rule face a dilemma with regard to implementation efforts.

The CFPB posted the Rule on its website on March 30, 2023. The October 1, 2024 implementation date for Tier One lenders (lenders that originated at least 2,500 small business loans in 2022 and 2023) is too aggressive. The April 1, 2025 implementation date for Tier Two lenders (lenders that originated at least 500, but less than 2,500, small business loans in 2023 and 2024) also is aggressive. The January 1, 2026 implementation date for Tier Three lenders (lenders that originated at least 100, but less than 500, small business loans in 2024 and 2025) is more reasonable.

A good comparison for the appropriateness of the implementation dates is the revisions to Regulation C, the rule implementing the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), released by the CFPB on October 15, 2015 (the revised rule appeared in the October 28, 2015 Federal Register). The revised rule was based on amendments to HMDA made by Dodd-Frank. As is the case with the Rule, Congress specified new HMDA data categories and also provided for the collection and reporting of “such other information as the Bureau may require.” The CFPB added significantly more data categories, with the result being that the 23 pre-existing HMDA data categories were more than doubled, and there were modifications to many of the pre-existing data categories.

In addition to the changes that the mortgage industry needed to make to comply with the new rule, the CFPB advised it would build an electronic portal and institutions would submit HMDA data online via the portal. Thus, not only did institutions have to revise their operations and systems to comply with the revised HMDA rule, their systems had to be designed in a manner that would provide for communication with the CFPB portal. Recognizing the significant task facing the mortgage industry, the CFPB provided for a primary implementation date of January 1, 2018, a period of more than 26 months, with the revised data first being reported by March 1, 2019. In the preamble to the final HMDA rule, the CFPB observed as follows:

“The Bureau believes that these effective dates, which provide an extended implementation period of over two years, is appropriate and will provide industry with sufficient time to revise and update policies and procedures; implement comprehensive systems change; and train staff. In addition, the implementation period will assist in facilitating updates to the processes of the Federal regulatory agencies responsible for supervising financial institutions for compliance with the HMDA rule.”

With regard to the Rule, in Dodd-Frank Congress specified 13 data categories plus “any additional data that the Bureau determines would aid in fulfilling the purposes of this section.” Based on additions made by the CFPB, the Rule has over 30 main data categories, with many categories having subcategories that increase the compliance burden. Additionally, lenders will report the small business loan data to the CFPB through an electronic portal being built by the CFPB. In contrast with the revised HMDA rule, the Rule does not require only modifications of operations and systems, it requires the creation of operations and systems from scratch. In short, the burden to implement the Rule is more significant than the burden to implement the revised HMDA rule. Yet, with the Rule the CFPB provided for implementation periods of approximately 18, 25 and 33 months for Tier One, Two and Three lenders, respectively. The first two implementation periods are too short. Thus, Tier One and Tier Two lenders not covered by the Texas court order could be facing the need to implement the rule in an unreasonably short period of time. While Tier One and Tier Two lenders covered by the Texas court order will benefit from delayed implementation dates, the delay simply may provide for a reasonable implementation period.

In short, even with the Texas and Kentucky court orders, Tier One and Tier Two lenders need to carefully assess the speed of their implementation efforts.

Last week, three farm credit trade associations filed the latest in a series of unopposed emergency motions for leave to intervene in the Texas case challenging the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) final small business lending rule implementing Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act (Rule). The intervenors – the Farm Credit Council, Texas Farm Credit, and Capital Farm Credit (collectively, “Farm Credit Intervenors”) – argue that the Rule imposes substantial burdens on agricultural lenders and the institutions that support them, and that the members they represent will suffer disproportionately, as the majority of their loans go to small businesses, such as farmers, ranches, and agribusinesses, covered by the Rule.

As we have previously discussed, other motions to intervene have been filed and the Texas federal court has already granted the motions for leave to intervene filed by community bank and credit union intervenors and the community bank intervenors have filed a preliminary injunction motion in which the credit union intervenors have joined. In their preliminary injunction motion, the community bank and credit union intervenors ask the Texas federal court to enter a preliminary injunction prohibiting the CFPB from enforcing the Rule nationwide or, alternatively, as to the intervenors and their members. Despite having already lost the argument that preliminary relief is not warranted as to the plaintiffs, the CFPB has opposed the intervenors’ preliminary injunction motion.

The Farm Credit Intervenors asked for expedited consideration of their motion, and, like plaintiffs and other intervenors, intend to file a motion for a preliminary injunction if their motion to intervene is granted. While the court has preliminarily enjoined the CFPB from implementing and enforcing the Rule “pending the Supreme Court’s reversal of [Community Financial Services Association of America Ltd. v. CFPB], a trial on the merits of this action, or until further order of this Court” for plaintiffs and their members, the court did not grant nationwide relief when it granted plaintiff’s preliminary injunction motion on July 31, 2023. As a result, we expect to see additional parties seeking to intervene in order to obtain injunctive relief from the Rule.

John L. Culhane, Jr., Richard J. Andreano, Jr., Michael Gordon, Alan S. Kaplinsky & Brian Turetsky

This past Thursday, August 31, another preliminary injunction motion was filed in the Texas lawsuit challenging the CFPB’s small business lending rule (Rule). The latest motion was filed by XL Funding, LLC d/b/a Axle Funding, LLC (Axle) and the Equipment Leasing and Finance Association (ELFA) (collectively, the ELFA Intervenors), following the court’s entry of an order granting their motion for leave to intervene and their filing of an intervenor complaint. The filing of the ELFA Intervenors’ preliminary injunction motion means there are now two new preliminary injunction motions pending before the Texas federal district court, with the community bank and credit union intervenors having filed their preliminary injunction motion on August 15 and the CFPB having filed its opposition on August 22.

This unfortunate situation has led many people to suggest that Director Chopra should unilaterally suspend, delay or stay the Rule’s compliance dates. However, Director Chopra does not appear to have this authority. Section 705 of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) permits an agency to postpone a rule’s effective date, without providing notice and an opportunity for public comment, if the rule is pending judicial review and “an agency finds that justice so requires.” Case law interpreting this APA provision is sparse. Federal district courts have generally allowed agencies to invoke Section 705 to postpone rules that are not yet effective. However, the Rule became effective on August 29 and courts have not allowed agencies to invoke Section 705 to postpone the compliance date of an already effective rule. Becerra v. U. S. Dep’t of Interior, 276 F. Supp. 3d 953, 965 (N.D. Cal. 2017 (holding that Department of Interior could not delay oil and gas valuation rule’s compliance dates after rule’s effective date of had passed); California v. I.S. Bureau of Land Management, 277 F. Supp 3d 1106, 1121 (N.D. Cal. 2017) (discussing Becerra, and noting that “[e]ffective and compliance dates have distinct meanings”); Nat. Res. Def. Council v. U. S. Dep’t of Energy, 363 F. Supp. 3d 126, 151 (S.D.N.Y. 2019).

More optimistically, although we have not found any relevant case authority, the text of APA Section 705 could be read to allow a federal district court to stay the compliance date and/or enjoin enforcement of a rule that has taken effect. Section 705 provides that “[o]n such conditions as may be required and to the extent necessary to prevent irreparable injury, the reviewing court…may issue all necessary and appropriate process to postpone the effective date of an agency action or to preserve status or rights pending conclusion of the review proceedings.” Thus, if so read, Section 705’s text would provide the Texas federal district court with an alternate source of authority for staying the Rule’s tiered compliance dates and/or enjoining the CFPB from enforcing the Rule on a nationwide basis pending the outcome of the CFSA case in the U.S. Supreme Court and the outcome of the underlying case before it. This clearly seems preferable to the patchwork approach of ruling on multiple preliminary injunction motions and limiting the injunctive relief only to the plaintiffs and intervenors.

Of course, as we have previously noted, the CFPB can quickly remedy the current situation by issuing a proposal to delay the Rule’s tiered compliance dates and allowing a 30-day comment period. It could then issue a final rule soon after the comment period ends.

As we predicted long ago, on Friday, September 8, 2023, the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Texas vacated the changes made in March 2022 to the CFPB’s Exam Manual. On that date, the CFPB purported to use its authority to prohibit unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices (UDAAPs) to target discriminatory conduct, even where fair lending laws may not apply. Specifically, the CFPB directed its examiners to apply the “unfairness” standard under the Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA) to conduct considered to be discriminatory, whether or not it is covered by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA)(such as in connection with denying access to a checking account). Under the CFPA, an act or practice is “unfair” if (1) it causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers, (2) the injury is not reasonably avoidable by consumers, and (3) the injury is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition. In its press release, the CFPB stated:

The CFPB will examine for discrimination in all consumer finance markets, including credit, servicing, collections, consumer reporting, payments, remittances, and deposits. CFPB examiners will require supervised companies to show their processes for assessing risks and discriminatory outcomes, including documentation of customer demographics and the impact of products and fees on different demographic groups. CFPB examiners will look at how companies test and monitor their decision-making processes for unfair discrimination, as well as discrimination under ECOA.

The CFPB’s blog post about the manual update provided an indication of some of the practices the CFPB would scrutinize using an “unfairness” analysis. As an example of a discriminatory practice that “fall[s] squarely within our mandate to address and eliminate unfair practices,” the blog post identifies “the widespread and growing reliance on machine learning models throughout the financial industry and their potential for perpetuating biased outcomes,” and specifically mentions “certain targeted advertising and marketing, based on machine learning models, [that] can harm consumers and undermine competition.” Observing that “[c]onsumer advocates, investigative journalists, and scholars have shown how data harvesting and consumer surveillance fuel complex algorithms that can target highly specific demographics of consumers to exploit perceived vulnerabilities and strengthen structural inequities,” the CFPB indicated that it would “be closely examining companies’ reliance on automated decision-making models and any potential discriminatory outcomes.”

After an unsuccessful attempt to convince the CFPB to withdraw its changes to the Exam Manual, the United States Chamber of Commerce and other trade associations filed a lawsuit against the CFPB in Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Texas seeking, among other things, a declaration that the Exam Manual changes are unlawful. The plaintiffs claimed that the manual update should be set aside because it violates the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) for the following reasons:

- The update exceeds the CFPB’s statutory authority in the Dodd-Frank Act. The CFPB cannot regulate discrimination under its UDAAP authority because Congress did not give the CFPB authority to enforce anti-discrimination principles except in specific circumstances. The CFPB’s statutory authorities consistently treat “unfairness” and “discrimination” as distinct concepts. (To demonstrate the compliance burdens resulting from the update, the plaintiffs allege that the CFPB has provided no guidance for regulated entities on what might constitute unfair discrimination or actionable disparate impacts for purposes of UDAAP. As examples of issues creating confusion, the plaintiffs allege that the CFPB has not identified what are protected classes or characteristics or what activities are not discrimination (such as those identified in the ECOA), and has not explained how regulated entities should conduct the sorts of assessments that the CFPB appears to be contemplating given existing prohibitions on the collection of customer demographic information.)

- The update is “arbitrary and capricious” because the CFPB’s interpretation of “unfairness” contradicts the historical use and understanding of the term. The plaintiffs allege that the FTC’s unfairness authority does not extend to discrimination and that Congress borrowed the FTC Act’s unfairness definition for purposes of defining the CFPB’s UDAAP authority. They also allege that the CFPB’s contemplated use of disparate impact liability when pursuing UDAAP claims flouts congressional intent and U.S. Supreme Court authority.

- The update violates the APA’s notice-and-comment requirement because it is a legislative rule that imposes new substantive obligations on regulated entities.

In addition to claiming that the Exam Manual update should be set aside due to the alleged APA violations, the plaintiffs allege that the update should be set aside because the CFPB’s funding structure violates the Appropriations Clause of the U.S. Constitution. (Pursuant to Dodd-Frank, the CFPB receives its funding through requests made by the CFPB Director to the Federal Reserve, subject to a cap equal to 12% of the Federal Reserve’s budget, rather than through the Congressional appropriations process.) As support for their unconstitutionality claim, the plaintiffs cite the concurring opinion of Judge Edith Jones in the Fifth Circuit’s en banc May 2022 decision in All American Check Cashing in which Judge Jones concluded that the CFPB’s funding mechanism is unconstitutional. (While the case was pending, the Fifth Circuit issued a unanimous opinion in a case entitled CFSA et al v. CFPB in which it agreed with Judge Jones’s concurring opinion mentioned above and held that the CFPB’s funding mechanism is unconstitutional and that its payday lending rule is invalid.)

The plaintiffs in the Chamber case subsequently filed a motion for summary judgment which was met with a dispositive motion by the CFPB. Initially, the Court rejected all of the CFPB’s arguments, including that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring the lawsuit, that the CFPB was immune from the lawsuit as a sovereign and that venue was improper in the Eastern District of Texas. While the CFPB conceded that the plaintiffs motion based on the CFSA case should be granted, it argued that the Court should not reach or decide any of the other arguments made by the plaintiffs in support of invalidating the Exam Manual changes. The Court disagreed and, instead, in a well-written opinion, explained why the Exam Manual changes were contrary to the UDAAP statutory authority. The Court had no need to, and did not, reach or decide the other two APA issues raised by the plaintiffs

The Court first dealt with two preliminary interpretive issues. First, it concluded that no Chevron deference should be given to the CFPB’s revisions to its Exam Manual. Because the CFPB did not request judicial deference, the Court concluded that the CFPB waived this potential argument. Second, the Court observed that “‘the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.’ That inquiry is ‘shaped, at least in some measure, by the nature of the question presented’—here, whether Congress meant to confer the power the agency asserts. Even if an agency’s ‘regulatory assertions had a colorable textual basis,’ a court must consider ‘common sense as to the manner’ in which Congress would likely delegate the power claimed in light of the law’s history, the breadth of the regulatory assertion, and the economic and political significance of the assertion.” [Footnotes omitted]

Based on these principles, the District Court relied upon the “major questions doctrine.” The major questions doctrine is a principle which states that courts will presume that Congress does not delegate to executive agencies issues of major political or economic significance. The “major questions doctrine” is derived from the Supreme Court opinion in FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. (2000): “[W]e must be guided to a degree by common sense as to the manner in which Congress is likely to delegate a policy decision of such economic and political magnitude to an administrative agency.” It was relied upon in a recent Supreme Court opinion in State of West VA v. Environmental Protection Agency where the Court “recognize[d] that sweeping grants of regulatory authority are rarely accomplished through ‘vague terms’ or ‘subtle device[s].’ Courts must ‘presume that Congress intends to make major policy decisions itself, not leave those decisions to agencies.’ If that major questions canon applies, ‘something more than a merely plausible textual basis for the agency action is necessary. The agency instead must point to clear congressional authorization for the power it claims.” The doctrine was also relied upon in Biden v. Nebraska where the Court likewise recognized that “the economic and political significance [of the agency’s forgiveness of federal student loans] is staggering by any measure” and that “the basic and consequential tradeoffs” that are necessarily part of the action “are ones that Congress likely would have intended for itself.”

The Court had no difficulty identifying the “major question” here. “The choice whether the CFPB has authority to police the financial-services industry for discrimination against any group that the agency deems protected, of for lack of introspection about statistical disparities concerning any such group, is a question of major economic and political significance.” The economic impact was demonstrated by the substantial sums of money (“millions of dollars per year”) spent by companies on compliance. The political implications included the impact on state and federal powers, since the CFPB would be overriding state decisions on discrimination issues, as well as the “profound” implications regarding the scope of federal power with regard to protected classes, prohibited outcomes, and defenses to claims of misconduct.

Against that backdrop, the Court found nothing in the Dodd-Frank Act to support the CFPB’s position. The Court agreed with the plaintiffs that discrimination and unfairness are treated as distinct concepts in the Act, noting, for example, the creation of a CFPB office devoted to “fair, equitable and nondiscriminatory access to credit” which references the Equal Credit Opportunity Act but makes no mention of unfairness and the statutory definition of unfairness which fails to mention discrimination. Looking to the text, structure of the Dodd-Frank Act, and the historical gloss on unfairness, the Court held that “the Dodd-Frank Act’s language authorizing the CFPB to regulate unfair acts or practices is not the sort of ‘exceedingly clear language’ that the major questions doctrine demands ….”

After concluding that the Exam Manual changes exceeded the CFPB’s UDAAP statutory authority, the Court vacated the changes to the Exam Manual. Curiously, the Court also granted an injunction against the CFPB preventing it from enforcing the changes in the Exam Manual against only members of the plaintiff trade associations.

Here are our observations and takeaways:

- We were surprised that the CFPB didn’t appear to argue that the case ought to be just stayed pending the outcome of the Supreme Court opinion in CFPB v. CFSA since many courts had done precisely that with respect to pending enforcement actions by the CFPB. While we expect that the trade associations would have opposed a stay since they were very anxious to obtain a ruling on the merits, the Court might very well have “kicked the can down the road.”

- The Court may have created some unnecessary confusion by issuing an injunction precluding the CFPB from enforcing the Exam Manual changes only against the plaintiffs and their members after it had previously vacated the Exam Manual changes in their entirety as to everyone effected by those changes. Once it vacated the Exam Manual changes, why did the Court decide to even bother with issuing injunctive relief? Once it decided to grant this additional and seemingly superfluous remedy, why did it confer the benefits only on the plaintiffs and their members? We assume that it did so to insure that the CFPB does not seek to bring any supervisory action or enforcement action against the plaintiffs under the now discredited theory that it can assert that allegedly discriminatory practices are unfair. However, by sowing this confusion, trade associations other than the plaintiffs may feel it necessary to seek to intervene in the lawsuit and seek their own injunctive relief to benefit their own members or they may feel it necessary to bring a separate suit seeking the same injunctive relief. That is, of course, precisely what has recently happened in the lawsuit brought by the American Bankers Association and Texas Bankers Association challenging the legality of the final rule recently promulgated under Section 1071 of Dodd-Frank dealing with mandatory data collection with respect to small business loans. See here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, & here for our blogs about the multiple interventions and preliminary injunction motions that the 1071 case has spawned. We don’t expect that to happen in this case since we very much doubt that the CFPB would investigate or bring an enforcement action against a company that is not covered by the injunction unless the CFPB is hoping to create a split in authority by suing in another Circuit, like the Second Circuit which has held that the CFPB’s funding is constitutional.

- We were surprised that the CFPB waived its argument that the Court should give judicial deference to the changes to the Exam Manual based on the Chevron case even though a case is pending before the Supreme Court which might overrule Chevron. Under the Chevron judicial deference doctrine, a court must validate an agency’s interpretation of a regulation if the statutory authority is ambiguous and the regulation is reasonable. (Perhaps the CFPB took this approach because it did not want to concede that the changes to the Exam Manual constituted a “rule” under the APA. However, the Court found against the CFPB on this issue.)

- While the Court did not directly rule on whether Section 5 of the FTC Act (which, like the CFPA, proscribes unfair and deceptive acts and practices) also encompasses discrimination claims, the Court certainly cast aspersions on the FTC’s conclusion that it does. Perhaps, the FTC will keep its powder dry for the time being in pursuing this theory.

- The big question is whether the CFPB will appeal to the Fifth Circuit. If the District Court had not vacated the changes to the Exam Manual, we don’t think the CFPB would appeal since its odds of prevailing in the Fifth Circuit (the home of CFSA v. CFPB and the most conservative Circuit Court in the country) would be very slim. An appeal could result in a Fifth Circuit opinion affirming the District Court on the merits and that, of course, would be much worse for them than this District Court opinion.

- The District Court opinion will have some impact on the anticipated lawsuit in the District Court in Texas against the CFPB challenging a final credit card late fee regulation based on the binding Fifth Circuit opinion in CFSA v. CFPB, but the more significant aspect of the opinion predicated on the “major questions doctrine” will not apply. That’s because the credit card late fee regulation is contemplated by the CARD Act and is not a creature of UDAAP.

- The highly anticipated “open banking” regulation is also not a creature of UDAAP but instead is authorized by a separate express provision in Dodd-Frank.

- This opinion will naturally result in the industry scrutinizing other pronouncements by the CFPB based on UDAAP as statutory authority. One obvious target is likely to be a Circular published in 2022 by the CFPB where it concluded that data security breaches resulting from a company’s negligence or malfeasance could be a UDAAP violation.

- We do not think that there is any reasonable possibility of Congress enacting legislation which would define UDAAP to encompass discrimination.

- While this case dealt with the “unfairness” prong of UDAAP and not the “abusive” prong of UDAAP, we would expect the industry to scrutinize any past or future explications of what the CFPB deems to be abusive to ensure that it passes muster under the “major questions doctrine.”

John L. Culhane, Jr., Michael Gordon, Richard J. Andreano, Jr. & Alan S. Kaplinsky

Yesterday, we blogged about the opinion issued on September 8 by the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Texas in the lawsuit brought last year by several trade associations against the CFPB. In that lawsuit, the trade associations challenged changes made by the CFPB to its UDAAP Exam Manual in March, 2022 to encompass discrimination claims within the “unfairness” prong even when such claims go well beyond the scope of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. The Court granted summary judgment to the plaintiffs on two of its claims: first, that the Exam Manual changes are contrary to the Fifth Circuit opinion in CFSA v. CFPB holding that the CFPB was and is unconstitutionally funded and that any rules issued by the agency necessarily draw on such funding and are thus invalid; and, second, that the Exam Manual changes are simply not authorized by the Dodd-Frank UDAAP provision given the “major questions doctrine” and the complete absence of the “exceedingly clear language” that the major questions doctrine demands for a finding that the UDAAP provision confers on the CFPB the authority to regulate discrimination across the financial services industry.

The Court then vacated in their entirety the Exam Manual changes. We then stated the following in yesterday’s blog: “Curiously, the Court also granted an injunction against the CFPB preventing it from enforcing the changes in the Exam Manual against only members of the plaintiff trade associations.”

Later in our blog, we made the following observations about this curiosity:

The Court may have created some unnecessary confusion by issuing an injunction precluding the CFPB from enforcing the Exam Manual changes only against the plaintiffs and their members after it had previously vacated the Exam Manual changes in their entirety as to everyone affected by those changes. Once it vacated the Exam Manual changes, why did the Court decide to even bother with issuing injunctive relief? Once it decided to grant this additional and seemingly superfluous remedy, why did it confer the benefits only on the plaintiffs and their members? We assume that it did so to insure that the CFPB does not seek to bring any supervisory action or enforcement action against the plaintiffs under the now discredited theory that it can assert that allegedly discriminatory practices are unfair. However, by sowing this confusion, trade associations other than the plaintiffs may feel it necessary to seek to intervene in the lawsuit and seek their own injunctive relief to benefit their own members or they may feel it necessary to bring a separate suit seeking the same injunctive relief. That is, of course, precisely what has recently happened in the lawsuit brought by the American Bankers Association and Texas Bankers Association challenging the legality of the final rule recently promulgated under Section 1071 of Dodd-Frank dealing with mandatory data collection with respect to small business loans…We don’t expect that to happen in this case since we very much doubt that the CFPB would investigate or bring an enforcement action against a company that is not covered by the injunction unless the CFPB is hoping to create a split in authority by suing in another Circuit, like the Second Circuit which has held that the CFPB’s funding is constitutional.

In retrospect, and after reviewing the briefs filed by the parties, we may have been a bit too sanguine about the CFPB not taking any further action against non-parties to the lawsuit based on its theory that discrimination is an “unfair” practice within the meaning of the Dodd-Frank UDAAP provision. In taking further action, the CFPB would not, of course, be relying on the Exam Manual changes (which the Court vacated), but rather on its purportedly “longstanding” interpretation of the “unfairness” prong of UDAAP as encompassing discrimination. Here is a relevant excerpt from one of the CFPB’s briefs submitted in opposition to the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgement:

The Exam Manual does not change the legal status of the parties, including by authorizing new topics of examination. The Dodd-Frank Act prohibited unfairness prior to the issuance of the Manual. 12 U.S.C. § 5536(a)(1)(B). There has never been an unstated, atextual exception to the prohibition on unfairness for discrimination, just as there is not an unstated exception to unfairness for conduct that happens on Leap Day. Nor were CFPB examiners, prior to March 2022, prohibited from examining regulated parties on the topics addressed in the revisions: the updates to the Manual provide a roadmap of additional preliminary factual assessments for examiners to make (depending on the scope of the particular examination), but examiners could have made those preliminary assessments without the updates. After all, the Manual does not provide the source of authority for those examinations—that authority derives primarily from statute. See 12 U.S.C. §§ 5514(a), 5515.

This totally explains why the plaintiffs felt it was necessary to seek an injunction. The plaintiffs asked for injunctive and declaratory relief to enjoin CFPB from using this new UDAAP interpretation in any context (i.e., investigative subpoena). Unfortunately, the court limited the injunctive/declaratory relief to members of the plaintiff trade associations, which as we noted in yesterday’s blog, creates confusion.

Notwithstanding the provocative language quoted above from the CFPB’s brief, we think that it is unlikely, but not beyond contemplation, that the CFPB could take supervisory or enforcement action against entities that are not beneficiaries of the injunction granted by the Court. Thus, it is certainly rational for non-parties (including additional trade associations) to consider filing intervention and injunction motions in the Texas lawsuit just as they have done in the other Texas lawsuit where a court limited its injunctive relief to just the plaintiff trade associations and their members. However, that is a time-consuming and costly process. As a result, we think that it would be appropriate for non-parties to adopt a “wait-and-see” approach and do nothing further unless and until word gets out that the CFPB, notwithstanding the Texas opinion, is continuing to take the position that it has the right to examine or investigate non-parties for discrimination based on the “unfairness “ prong of UDAAP. We will be very surprised if the CFPB engages in such selective enforcement of the CFPB’s interpretation of the “unfairness” prong of UDAAP in light of the strong rejection of that interpretation by the Texas court. That would certainly be very unfair.

John L. Culhane, Jr., Michael Gordon, Richard J. Andreano, Jr. & Alan S. Kaplinsky

We first review the Fair Credit Reporting Act provisions that establish the different requirements for how a creditor or other furnisher of information to a credit bureau must respond to direct and indirect identify theft disputes involving credit report information reported by the furnisher to a credit bureau. A direct dispute is one made directly by the consumer to the furnisher and an indirect dispute is one made by the consumer to the credit bureau and then submitted to the furnisher by the credit bureau. In particular, we focus on the information that a furnisher may require from a consumer before investigating each type of dispute. We then look at the factors courts have considered in decisions involving whether, in connection with an indirect identity theft dispute, a furnisher satisfied the FCRA requirement to conduct a reasonable investigation. We conclude with a discussion of best practices for furnishers to consider when handling investigations of indirect identity theft disputes.

Alan Kaplinsky, Senior Counsel in Ballard Spahr’s Consumer Financial Services Group, leads the conversation joined by Melanie Vartabedian and Joel Tasca, partners in the Group.

To listen to the episode, click here.

CPPA Publishes New Draft Regulations Addressing AI, Risk Assessments, Cyber Audits

The California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) recently published two new sets of draft regulations addressing a range of cutting-edge data protection issues. Although the CPPA has not officially started the formal rulemaking process, the Draft Cybersecurity Audit Regulations and the Draft Risk Assessment Regulations will serve as the foundation for the process moving forward. Discussion of the draft regulations will be a central topic of the CPPA’s upcoming September 8 meeting.

Among the noteworthy aspects to the draft Regulations are (1) a proposed definition of “artificial intelligence” that differentiates the technology from automated decision-making; (2) transparency obligations for companies that train AI to be used by consumers or other businesses; and (3) a significant list of potential harms to be considered by businesses when conducting risk assessments.

The Draft Cybersecurity Audit Regulations make both modifications and additions to the existing California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) regulations. At a high level, the draft regulations:

- Outline the requirement for annual cybersecurity audits for businesses “whose processing of consumers’ personal information presents significant risk to consumers’ security”;

- Outline potential standards used to determine when processing poses a “significant risk”;

- Propose options specifying the scope and requirements of cybersecurity audits; and

- Propose new mandatory contractual terms for inclusion in Service Provider data protection agreements.

Similarly, the Draft Risk Assessment Regulations propose both modifications and additions to the existing CCPA regulations. The draft regulations:

- Propose new and distinct definitions for Artificial Intelligence and Automated Decision-making technologies;

- Identify specific processing activities that present a “significant” risk of harm to consumers, requiring a risk assessment. These activities include:

- Selling or sharing personal information; processing sensitive personal information (outside of the traditional employment context); using automated decision-making technologies; processing the information of children under the age of 16; using technology to monitor the activity of employees, contractors, job applicants, or students; or

- Processing personal information of consumers in publicly accessible places using technology to monitor behavior, location, movements, or actions.

- Propose standards for stakeholder involvement in risk assessments;

- Propose risk assessment content and review requirements;

- Require that businesses that train AI for use by consumers or other businesses conduct a risk assessment and include with the software a plain statement of the appropriate uses of the AI; and

- Outline new disclosure requirements for businesses that implement automated decision-making technologies.

Philip N. Yannella, Gregory P. Szewczyk & Timothy Dickens

CFPB Annual CARD Act, HOEPA, QM Adjustments Do Not Include Credit Card Penalty Fees Safe Harbors

The CFPB recently posted on its website a final rule regarding various annual adjustments it is required to make under provisions of Regulation Z (TILA) that implement the CARD Act, HOEPA, and the ability to repay/qualified mortgage provisions of Dodd-Frank. The adjustments reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in effect on June 1, 2023 and will take effect January 1, 2024. The adjustments do not include adjustments to the credit card penalty fees safe harbor.

Last year the CFPB published the annual adjustments late in December, prompting criticism from the industry and our firm, as the adjustments became effective on January 1, 2023.

CARD Act. Regulation Z provides for the CFPB to annually adjust (1) the minimum interest charge threshold that triggers disclosure of the minimum interest charge in credit card applications, solicitations and account opening disclosures, and (2) the penalty fees safe harbor amounts.

In the notice, the CFPB announced that the calculation did not result in a change for 2024 to the current minimum interest charge threshold (which requires disclosure of any minimum interest charge above $1.00). (An increase in the minimum interest charge requires the change in the CPI to cause an increase in the minimum charge of at least $1.00.)

As was the case with the adjustments for 2023, the notice does not mention the credit card penalty fees safe harbors, which are set forth in Regulation Z Section 1026.52(b)(1)(ii)(A) and (B). Section 1026.52(b)(1)(ii)(D) provides that that these amounts “will be adjusted annually by the Bureau to reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index.” For purposes of determining whether to make an adjustment in the minimum interest charge threshold, the CFPB used the CPI for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI–W), which increased by 4.6 percent over the relevant period, significantly less than the 8.9 percent increase used to compute the 2023 adjustments. Since the CFPB has also used the CPI-W when making past adjustments to the penalty fees safe harbor amounts, an adjustment for 2024 to the safe harbor amounts using the CPI-W presumably would reflect the 4.6 percent and 8.9 percent increases. The safe harbor amounts were last adjusted for inflation in 2022, and are $30 for a first late payment and $41 for each subsequent late payment.

In February 2023, the CFPB posted on its website a proposed rule regarding credit card late fees. The CFPB is proposing to amend Regulation Z to reduce the safe harbor dollar amount for credit card late fees to a flat $8 amount that would apply to both first and subsequent late payments.

HOEPA. Regulation Z provides for the CFPB to annually adjust the total loan amount and fee thresholds that determine whether a transaction is a high cost mortgage. In the final rule, for 2024, the CFPB increased the total loan amount threshold to $26,092, and the points and fees threshold to $1,305. As a result, in 2024, under the points and fees trigger a transaction will be a high-cost mortgage (1) if the total loan amount is $26,092 or more and the points and fees exceed 5 percent of the total loan amount, or (2) if the total loan amount is less than $26,092 and the points and fees exceed the lesser of $1,305 or 8 percent of the total loan amount.

Ability to repay/QM rule. The CFPB’s ability to repay/QM rule provides for the CFPB to annually adjust the points and fees limits that a loan cannot exceed to satisfy the requirements for a QM. The CFPB must also annually adjust the related loan amount limits. In the final rule the CFPB increased these limits for 2024 to the following:

- For a loan amount greater than or equal to $130,461, points and fees may not exceed 3 percent of the total loan amount;

- For a loan amount greater than or equal to $78,277 but less than $130,461, points and fees may not exceed $3,914;

- For a loan amount greater than or equal to $26,092 but less than $78,277, points and fees may not exceed 5 percent of the total loan amount;

- For a loan amount greater than or equal to $16,308 but less than $26,092, points and fees may not exceed $1,305; and

- For a loan amount less than $16,308, points and fees may not exceed 8 percent of the total loan amount.

Additionally, under the general qualified mortgage requirements, to be a QM the annual percentage rate on the loan may not exceed the average prime offer rate by a specified percentage, which varies based on the loan amount, lien status and home type. A number of the loan amounts used for the points and fees trigger also are used for this purpose. In 2024, to be a QM the annual percentage rate on the loan may not exceed the average prime offer rate by:

- 2.25 or more percentage points for a first lien loan with a loan amount greater than or equal to $130,461;

- 3.5 or more percentage points for a first lien loan with a loan amount greater than or equal to $78,277 but less than $130,461;

- 6.5 or more percentage points for a first lien loan with a loan amount less than $78,277;

- 6.5 or more percentage points for a first lien loan on a manufactured home with a loan amount less than $130,461;

- 3.5 or more percentage points for a subordinate lien loan with a loan amount greater than or equal to $78,277;

- 6.5 or more percentage points for a subordinate lien loan with a loan amount less than $78,277.

Amendments to Ohio’s Administrative Rules Relating to Residential Mortgage Lending

The Ohio Department of Commerce, Division of Financial Institutions is amending the rules that implement the state’s Residential Mortgage Lending Act. The Division is seeking preliminary feedback on the administrative rules, which are codified in the Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 1301:8-7, as they undergo a five-year rule review. Proposed updates will ensure the rules reflect amendments that were made to the Act in 2021.

The Division proposes to amend some key definitions of the rules, to reflect that the rules apply to mortgage lenders, mortgage loan originators, and mortgage brokers, while removing all references to mortgage bankers. A mortgage loan originator would continue to include someone who takes or offers to take residential mortgage loan applications or performs clerical or support duties of a loan processor or underwriter. However, the proposed amendment to the definition of mortgage loan originator would exclude assisting borrowers in obtaining mortgage loans, offering or negotiating terms, and issuing commitments. The rules would continue to apply to mortgage lenders and brokers, as those terms are defined in the Ohio Revised Code § 1322.01. However, the definition and all references to mortgage bankers would be removed from the rules.

Among other updates, the draft includes the following noteworthy proposed amendments:

- Amending the definition of “advertisement” to include web pages and social media posts, and excluding de minimis promotional items such as pens and mugs;

- Removing the requirements for registrants to maintain a physical office in the state and to maintain office hours;

- Removing the requirement for an applicant to be a licensee to have a sponsorship request submitted via the NMLS on his or her behalf;

- Removing the prohibition for registered MLO’s to complete transactions for second mortgages;

- Removing the requirement for a registrant or exempt entity to keep a complete signed copy of every final settlement statements for every residential mortgage loan;

- Removing the mortgage loan originator disclosure, and simplifying the requirements for the affiliated business disclosure;

- Amending the prohibited practices rule to include evading the limits on points and fees for qualified mortgages by conducting business in conjunction with a person registered or who should be registered as a Credit Services Organization;

- Amending the rule for nonprofit organizations to include the requirement for such organizations to be registered with the Charitable Law Section of the Ohio Attorney General’s Office and possess a valid letter of exemption;

- Amending the rule for loan processor and underwriting companies regarding the standards for requesting an exemption.

In addition to the proposed amendments, the Division intends to repeal the following rules in their entirety:

- Rule 1301:8-7-05. Special account requirements – Requires registrants to establish and maintain a non-interest-bearing, depository special account in the name of the registrant as it appears on its certificate of registration.

- Rule 1301:8-7-27. Expedited hearing upon automatic suspension – Requires an order of suspension to set a date, not more than 30 days later than the date of the order of suspension, for a hearing on the continuation or termination of such suspension.

- Rule 1301:8-7-30. Temporary loan originator license application – Outlines the standards for receiving and maintaining a temporary loan originator license.

The Division requests that stakeholders offer commentary or feedback on the proposed amendments by September 22, 2023, by emailing WebDFI-CFRules@com.ohio.gov.

Lisa Lanham & Loran Kilson

Yesterday, I moderated a live and virtual program at the American Bar Association Business Law Section 2023 Fall Meeting in Chicago. The program was entitled: “U.S. Supreme Court to Revisit Chevron Deference: What the SCOTUS Decision Could Mean for CFPB, FTC and Federal Banking Agency Regulations.” My co-panelists were Professor Jonathan S. Masur from the University of Chicago Law School and Lauren Campisi from Hinshaw & Culbertson.

In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, No. 22-451, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case in which the petitioners are challenging the continued viability of the Chevron framework that courts typically invoke when reviewing a federal agency’s interpretation of a statute. The Chevron framework derives from the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U. S. 837. Under the Chevron framework, a court will typically use a two-step analysis to determine if it must defer to an agency’s interpretation. In step one, the court looks at whether the statute directly addresses the precise question before the court. If the statute is ambiguous, the court will proceed to step two and determine whether the agency’s interpretation is reasonable. If it determines that the interpretation is reasonable, the court must defer to the agency’s interpretation.

The petition for certiorari was filed by four companies that participate in the Atlantic herring fishery. The companies had filed a lawsuit in federal district court challenging a National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) regulation that requires vessels that participate in the herring fishery to pay the salaries of the federal observers that they are required to carry. The Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) authorizes the NMFS to require fishing vessels to carry federal observers and sets forth three circumstances in which vessels must pay observers’ salaries. Those circumstances did not apply to the Atlantic herring fishery.

Applying Chevron deference, the district court found in favor of NMFS under step one of the Chevron framework, holding that the MSA unambiguously authorizes industry-funded monitoring in the herring fishery. The district court based its conclusion on language in the MSA stating that fishery management plans can require vessels to carry observers and authorizing such plans to include other “necessary and appropriate” provisions. While acknowledging that the MSA expressly addressed industry-funded observers in three circumstances, none of which implicated the herring fishery, the court determined that even if this created an ambiguity in the statutory text, NMFS’s interpretation of the MSA was reasonable under step two of Chevron.

A divided D.C. Circuit, also applying the two-step Chevron framework, affirmed the district court. The majority concluded that under step one of Chevron, the statute was not “wholly unambiguous,” and left “unresolved” the question of whether NMFS can require industry to pay the costs of mandated observers. Applying step two of Chevron, the majority concluded that NMFS’s interpretation of the MSA was a “reasonable” way of resolving the MSA’s “silence” on the cost issue.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to consider the second question presented in the companies’ petition for certiorari. That question is:

Whether the Court should overrule Chevron or at least clarify that statutory silence concerning controversial powers expressly but narrowly granted elsewhere in the statute does not constitute an ambiguity requiring deference to the agency.

The takeaways from our program were:

- Industry generally favors the Chevron doctrine because it creates more certainty which leads to a more stable business environment.

- The panelists believe that the Court will overrule the 1984 Chevron framework. The Supreme Court has not cited Chevron in many years and is very suspicious of administrative agencies. In various cases, the Supreme Court has eroded the Chevron framework.

- There are hundreds of cases where courts have validated federal agency regulations based exclusively on Chevron deference, including many cases in the Supreme Court. One of the cases is the 1996 Supreme Court opinion (Citibank, N.A. v. Smiley) upholding the validity of an OCC regulation defining “interest” under Section 85 of the National Bank Act to include late fees on loans.

- It is unclear whether such regulations would be subject to further attack and whether the courts would uphold their validity based on stare decisis. The Supreme Court in Raimondo is unlikely to provide any guidance about those earlier opinions that have validated regulations based exclusively on Chevron.

- There is likely to be increased litigation challenging past and future federal agency regulations and more of those regulations will be invalidated by courts.

If you missed this program, you should consider watching the recording.

CFPB Highlights Applicable HUD-Issued RESPA Guidance

The CFPB published guidance to remind the mortgage industry of numerous U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) policy statements that were issued before the CFPB assumed authority for enforcing the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA). The CFPB reiterates that official guidance documents issued by other agencies prior to the 2011 transfer would be applied by the CFPB unless they were superseded by law.

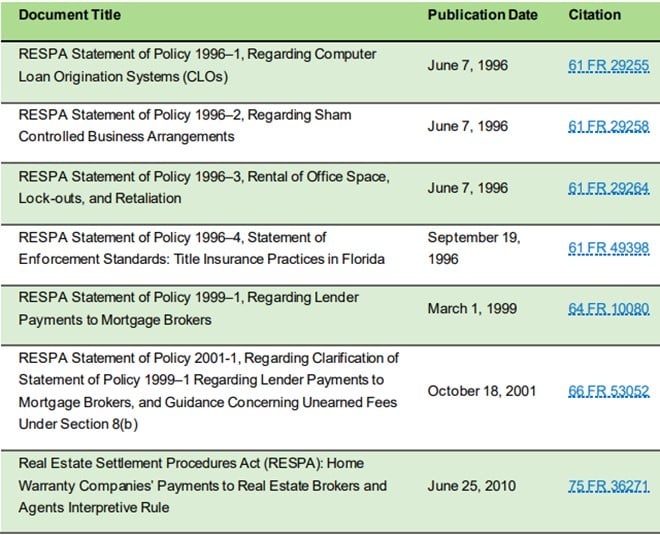

The CFPB states the following HUD documents continue to be applied today, and the CFPB notes that the list is not exhaustive of all HUD documents that continue to apply:

In the guidance the CFPB references, and includes a link to, a July 2011 Transfer of Authorities Notice, in which the CFPB confirmed rules and related regulatory actions issued by other agencies that were transferring to the CFPB. With regard to policy statements, that Notice provided “the CFPB notes that for laws with respect to which rulemaking authority will transfer to the CFPB, the official commentary, guidance, and policy statements issued prior to July 21, 2011, by a transferor agency with exclusive rulemaking authority for the law in question (or similar documents that were jointly agreed to by all relevant agencies in the case of shared rulemaking authority) will be applied by the CFPB pending further CFPB action.” Over the years, statements made by, and positions taken by, the CFPB reflected that it was applying the guidance set forth by HUD in the listed policies, such as Statement of Policy 1996-2, Regarding Sham Controlled Business Arrangements (which are now referred to as “affiliated business arrangements”).

CFPB Director Rohit Chopra Addresses Mortgage Post-Crisis Reforms and Importance of Consumer Protection Regulations

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) Director Rohit Chopra recently addressed The Mortgage Collaborative National Conference recounting the Congressional response to the mortgage industry crisis that began in 2008 that resulted in the creation of the CFPB. Mr. Chopra emphasized that challenges to the validity and authority of the CFPB could hurt the stability of the U.S. housing market and broader consumer protections.

Mr. Chopra’s remarks began with a brief history of the 2008 mortgage market crash, and how the actions of IndyMac Bank resulted in one of the largest ever bank failures managed by the FDIC. In response, Congress shook up the federal financial regulators by shutting down the Office of Thrift Supervision and stripping authorities from a number of banking regulators, transferring these authorities to the CFPB.

Based on this shift in protection, Mr. Chopra highlights that the CFPB established new standards for ensuring borrowers have the ability to repay through the ability to repay/qualified mortgage rule. Further, other regulators responsible for the standards for mortgage securitization largely “duplicated” the standards of the CFPB. Moreover, CFPB’s implemented mortgage rules mandated by Congress are now “built into the entire fabric” of the U.S. mortgage system, “including marketing, origination, securitization, and servicing.” Mr. Chopra stressed that these rules not only provide clarity, they have restored trust in the mortgage system.

Mr. Chopra warned that the recent court challenges to the constitutionality of the CFPB rules based on its receiving funding from the Federal Reserve System and not Congressional appropriations could have significant implications for the entire housing finance and financial regulatory system. Mr. Chopra maintains that the CFPB is just one part of the structure and not the only agency funded this way. He asserts that any doubt about the legitimacy of the CFPB could be “destabilizing.”

Citing to the recent Supreme Court amici brief filed by the Mortgage Bankers Association and other trade associations, Mr. Chopra emphasized that calling into question CFPB rules could have “potential catastrophic consequences on the mortgage and real-estate markets.” Mr. Chopra warns that reverting to a system without CFPB regulations would create uncertainty for the mortgage industry and the economy, concluding that “even putting aside the questions about existing rules, moving to a world where the future of housing finance oversight is uncertain and unknown…should raise serious shared trepidations among market participants, financial markets, and consumers alike.”

Notably, Mr. Chopra’s remarks were issued contemporaneously against the backdrop of a recent decision by the Federal District Court of the Eastern District of Texas vacating the March 2022 changes made by the CFPB to its UDAAP Exam Manual on the grounds that the funding mechanism of the CFPB is unconstitutional and that the changes exceeded the CFPB’s statutory authority.

In preparation for renewals, the NMLS has released a “quick start” guide regarding the individual renewal process. The guide also has an FAQ, which addresses a variety of required steps for MLOs, such as state-specific continuing education requirements.

Subscribe to Ballard Spahr Mailing Lists

Copyright © 2026 by Ballard Spahr LLP.

www.ballardspahr.com

(No claim to original U.S. government material.)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author and publisher.

This alert is a periodic publication of Ballard Spahr LLP and is intended to notify recipients of new developments in the law. It should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. The contents are intended for general informational purposes only, and you are urged to consult your own attorney concerning your situation and specific legal questions you have.